The rising star of the spirits world is only for the brave.

The people who prefer spirits over other alcoholic categories like beer and wine make that claim because they enjoy biting strength and complex flavours and aromas that can take an entire evening to unravel. But in the face of China’s baijiu, even the steeliest nose and palate may falter. The country’s (in)famous firewater is the most consumed spirit in the world, but its pungent aroma and sharp character slowed its spread outside of the Middle Kingdom. Not anymore.

Baijiu’s origins are murky, with some estimates citing AD960 as the time that ancient distilled spirits started to resemble modern baijiu. But its past isn’t as exciting as its future. When Futurebrand Index 2018 released its global perception study on how future-proof the world’s top 100 prominent companies were, newcomer Kweichow Moutai came in second, after The Walt Disney Company. It also tied with Apple for first place on the list of companies that create products consumers would pay more for.

And, boy, are they willing to fork out the big bucks. An 80-year-old bottle made by Kweichow Moutai in 1940 was auctioned off last July for 1.97 million yuan (S$395,000). For comparison, an entire case of 1988 Domaine de la RomaneeConti, one of the most prestigious wines in the world, sold for £264,000 (S$460,000) last March.

Of course, there’s more to baijiu than the partially state-owned Kweichow Moutai brand. Just like whisky and wine, different provinces are known for different styles, and tweaking even one part of the baijiu-making process will yield wholly distinct results. You don’t have to be part of China’s elite to partake in this imposing drink; just keep your portions as humble as your demeanour and ready your senses for the adventure that awaits.

01 SHUI JING FANG FOREST GREEN

When Chengdu’s Quanxing Distillery unearthed ancient fermentation pits and production equipment from the Ming and Qing dynasties, it harvested the bacteria from those pits to make its premium Shui Jing Fang strong aroma baijiu. Forest Green uses charcoal and bamboo filtering to create a more delicate aroma and smoother taste.

02 WU LIANG YE

According to the 2018 Brand Finance Spirits 50 report, Wu Liang Ye was the fastest-growing brand on the list, growing 161 per cent year-onyear to US$14.6 billion (S$19.8 billion). The baijiu gets its name from the five grains from which it’s distilled: proso millet, maize, glutinous rice, longgrain rice and wheat. It has a slightly sweet and fruity aftertaste.

03 HONG XING ER GUO TOU

04 LUZHOU LAOJIAO ZI SHA

Luzhou Laojiao is one of the four oldest distilleries in China, with a history dating back to the Ming dynasty, thus earning the company China’s Tangible Cultural Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage awards. The Zi Sha edition is named for its traditionally styled, purple porcelain bottle. Fun fact: The Australian Open landed a partnership deal with the distillery last October, making it the largest Chinese sponsorship in the history of the tournament.

05 HONG XING ER GUO TOU ZHEN CHANG

BYEJOE

TAIZI

HOW IT’S MADE

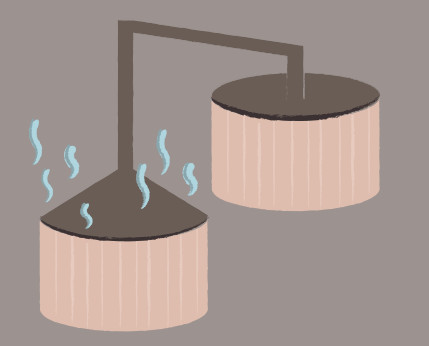

04 DISTILLATION

Western spirits are aged in wooden casks to impart flavour, but baijiu is left in earthenware urns so that it will oxidise and mellow out. Lower-end brands will opt to mature their spirits in stainless steel tanks, but clay is generally preferred because its porosity allows the distillate to better interact with its environment. The ageing containers are stored in underground cellars, caves or any dark room for at least a year.

Baijiu styles are categorised by aroma. Here are the main ones to know.

Its lighter, sweeter flavour means rice aroma baijiu are the most accessible for those new to the spirit. Originating from and found almost exclusively in southern China, this type is made with long-grain rice and/or glutinous rice and has a clean aftertaste, making it comparable to Japanese shochu or even sake. It is aged in limestone caves and often infused with medicinal herbs, flowers or tea to give it a sweeter flavour. Lao Guilin and Guilin Sanhua Jiu are popular makers of rice aroma baijiu.

Don’t let the name fool you. Light aroma baijiu might be gentle on the nose but it is typically bottled at a high ABV – 60 per cent ABV is not uncommon in this category. Its main ingredient is sorghum and is traditionally fermented in ceramic jars and distilled in pits. Light aroma baijiu hails from the north, around the Beijing area, and is favoured for its mild, floral sweetness. There are two main sub-divisions: er guo tou from Beijing, and fenjiu from the Shangxi province. The differences lie in the type of qu used.

For a province known for fiery cuisine, it’s not surprising that strong aroma baijiu is most commonly associated with Sichuan. Because it is made with at least two different grains, this type of baijiu exhibits more complex flavours and aromas. Fragrant, well-balanced, and with an almost boundless finish, this style is the biggest category of baijiu by market share and volume and accounts for more than two thirds of all baijiu production. Big names in this category include Luzhou Laojiao, Shui Jing Fang, Jiangnanchun and Yanghe.