WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE ASIAN? THAT QUESTION IS SO LARGE, SO VAST, THAT ANSWERING IT IS NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE ASIAN? THAT QUESTION IS SO LARGE, SO VAST, THAT ANSWERING IT IS NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE. THE TRUTH IS THAT SINGAPOREANS TODAY STRADDLE MULTIPLE CULTURAL IDENTITIES: OUR OWN ETHNIC HERITAGE, OUR PLACE IN THE WORLD AS GLOBAL CITIZENS AND OUR COMMUNAL SENSE OF A NATION. SO INSTEAD OF TRYING TO FIND AN UNATTAINABLE ANSWER, WE WENT IN SEARCH OF THE PARTICULAR.

ELIZABETH GABRIELLE LEE

“I’m interested in the notion of slow violence,” says Elizabeth Gabrielle Lee. The term, which was originally used to describe violence on the climate, has been borrowed by the 26-year-old to apply to postcolonialism and how it influences the spaces we live in. Space is an especially important part of this equation – Lee, a Singaporean, lives and works in London.

Her most recent and ongoing work, We’ve Got The Sun Under Our Skin, is a photographic series that inverts the colonial gaze. It’s based on colonial literature about Malaya from the 1800s by British ethnologists and anthropologists who were recording the region’s people, flora and fauna. “The language is alarming. Landscapes, women and people were fetishised,” Lee says of the texts she found.

She proceeded to tear pages from these source texts, scrawled out portions of it – leaving in relevant passages – then set to work lensing these subjects in her own way. “In a primal sense, it felt like I was trying to reclaim these landscapes and people,” she says.

“There’s a weird double bind,” she admits of the project. The “weird, imperial” gaze is simultaneously reproduced and reversed, and the work confronts notions of who controls and produces knowledge, and the effects that language can have on our modern identities. These colonial writers brought their wildly ornamental accounts back to the West, and Lee describes her work as a similar violence of erasure that she is enacting on imperial history.

That’s not to say, however, that she takes such a retributional approach to our colonial history. “It’s an attempt to resurface things from a new perspective and address the colonial past,” she explains. Leaving the work open for a viewer to interpret is critical to Lee, who says her approach avoids “prescriptivism and using completion as a black and white” marker. That liminal space for one to decide whether the work is more critique or an alternative form of presentation prevents – in her words – an “essentialism that puts representation in a pigeonhole”.

Lee’s 2018 project, The Unusual Powers Of Disposing, deals with a similar idea of subverting perspectives. That work stems from research around Christmas Island, where colonial British rulers used indentured labour to mine tricalcium phosphate, a profitable natural resource. In it, she offers visual intervention by juxtaposing stills from a corporate video by a mining company that works off the island with archival imagery of the mining sites and work conditions in the ’20s as well as text from the company’s own documents. The result is quietly damning.

Lee had in fact stumbled upon the subject of Christmas Island and phosphate mining by chance when she was looking up her own ancestry based on oral history about her great-grandfather. When she looked into the British archives, she found instead this history of the island that had been “tucked away and never dealt with”. As for her great-grandfather? “I found nothing. I guess it’s a way of me grieving and reacting to what I found in his place.”

FAIYAZ KOLIA

The work of this young photographer/art director, who prefers to be known as Faiyaz (or @fixated_f if you’re following his work on Instagram), has its lens firmly fixed on matters of race, representation and beauty – specifically around South Asian subjects. He recalls first realising in 2013 the existence of an issue while working on test shoots with local modelling agencies: “All the girls the agency were sending me were white. At the time, even Chinese girls were rare – and even they were usually mixed.”

Then – during 2014 to 2018, when he lived in London for his studies – he noticed a difference in how matters of race and racism tend to be confronted and discussed there and back home. In Singapore, it’s a topic that people often push aside and pretend doesn’t exist, says Faiyaz, who is of Gujarati and Sinhalese descent. “How can you live in a world where you don’t see yourself represented in everyday media? It’s weird.” That has led to his personal practice of using South Asian people in his work as a creative as far as he can.

When he first started doing so, he didn’t think much of it beyond a small, personal contribution. In the absence of agency-represented South Asian models, he found subjects in friends and people online whom he reached out to. That in turn resulted in a shift away from more traditional fashion photography, which – as he puts it – is intended to “simply create glamorous, beautiful imagery”.

“I started to resonate more with documentary photographers, photojournalists and even architecture photographers,” he explains. His approach became less about the construction of a premeditated image and more about the exploratory process of portraiture and the search for subjects less photographed.

There’s an unmistakable romanticism about Faiyaz’s images. He wants his work to be “an escape from reality” and Bollywood is a prominent reference. “I love the extravagant sets and the use of colour,” he gushes. “In the ’60s up till the ’80s, movie posters and billboards were hand-painted and had this dreamy quality: a bit cartoonish, but also a bit realistic. I try to recreate that vibe.”

More than just a surface quality, however, what Faiyaz is after using this sort of fantastical image-making is to give confidence to his subjects. “Even though I’m capturing real people, I want it to be a fantasy for them. That shows through more than the makeup and clothes they have on.”

His method and process of shooting also demonstrate a portrait artist’s interest in what’s beyond appearances. “For a lot of shoots, I’ll get the subject to bring in their own stuff: their mum’s jewellery, a tray or a pot, something with sentimental value.” This, he says, not only helps to make the sitters more comfortable, but also gives them a conversational point and adds dimensions of both past and present – all elements he’s interested in capturing.

Among young creatives here, the 27-year-old’s approach to representation is simultaneously obvious and radical, and makes him one of the most distinct names pushing actively for diversity in photography. He’s quick to wave off the notion though.

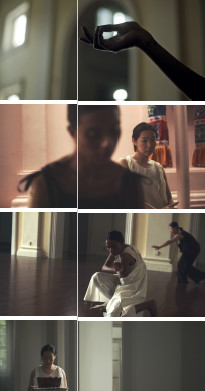

ALECIA NEO

When artist Alecia Neo talks about her work, the words that recur are “world-building”, “hospitality” and “care”. These are nebulous ideas that – put plainly – are tricky to translate. But it is with these lenses that the 34-year-old is looking at pertinent questions such as who is and isn’t welcome in society; how we conceive of and navigate the spaces we live in and share; and the rituals we choose to enshrine or leave behind.

The last of these is a central thought in her most recent work Ramah-Tamah for the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM). It’s a moody, pensive film that centres around South-east Asian betel nut rituals. Betel chewing is a nearly extinct practice now (the dark stains on the teeth and the practice of spitting were strongly discouraged for being public eyesores) yet has a long history in the hospitality rituals of the region. What’s interesting to Neo is that these rituals “have many circles of origin”. “They were possibly discovered simultaneously and developed at the same time,” she says.

Showcased in the middle of the year as part of the ACM’s Singapore Heritage Festival, Ramah-Tamah starts with real-life stories before narrowing into a focus on the stories of women who practiced betel chewing. “There’s so much to learn: the rituals and their significance. Rejecting or welcoming someone depends on whether you’re offered the betel, how objects are presented and turned. It’s a whole system of codes,” explains Neo. This symbolic language has all but disappeared here and Neo mentions accounts from her research of women who these days have swopped the public for the private, transforming the practice into something they do in their own rooms.

Hospitality is a key concern and the complexities Neo’s most interested in have to do with power relations: who plays host and guest? In Singapore, those questions can be said to relate to matters of migration, tourism and the reckoning that we have had recently with the treatment of migrant workers. In a country with an ethnic majority of Chinese settlers, the question of who we welcome and accept is not always an answered one and that naturally brings up a question of identity: If there’s an “us”, there’s a “them”.

The formation of our identities has to do with our history and heritage and what Neo is interrogating in her work is which of these one decides is relevant or to forget. She is not interested in nostalgia though.

“Culture and tradition cut both ways. They can encourage empowerment or limit and be a form of control,” she points out. What instead excites her is how we might find new ways of understanding our history and embracing the freedom of being able to redefine ourselves with a legacy of multiculturalism. “We’re discovering complex histories with no linear line and at the core, it’s about embracing diversity and not being afraid of it.”