THE PAST 12 MONTHS HAVE SEEN IMMENSE DEVELOPMENTS IN CURING THE PLASTIC PLAGUE. COULD THIS MEAN THE FUTURE OF OUR OCEANS MAY NOT BE AS DEPRESSING AS MANY HAVE THOUGHT?

THE PAST 12 MONTHS HAVE SEEN IMMENSE DEVELOPMENTS IN CURING THE PLASTIC PLAGUE. COULD THIS MEAN THE FUTURE OF OUR OCEANS MAY NOT BE AS DEPRESSING AS MANY HAVE THOUGHT?

AN INDIAN MAN IN a collared white-and-beige shirt begins his three-minute-and-forty-second video offering bleak, hard facts about plastic-use in his country, such as 120 billion pieces of disposable plastic cutlery discarded annually in a nation that predominantly eats with hands. But he has a solution: in a thick accent, he proposes a new cutlery, one that he proceeds to chew on followed by a few whimsical taps against his soup bowl to show that his spoon, though doused in broth, remains crunchy.

The man is Narayana Peespaty, chemist and associate research director at AC Nielsen The spoon he’s chewing on is made of millets, rice and wheat – preservative-free, vegan, 100% edible and the brainchild of his latest venture, Bakeys. Founded in 2011 in Hyderabad, Bakeys launched on Kickstarter this March. In a mere month, it raised close to US$280,000. Peespaty is now working on a full range of cutlery, which includes everything from ladles and chopsticks to bowls and coffee stirrers, set to launch by 2017.

Also in March, Icelandic product design student Ari Jónsson came up with a biodegradable drinking-bottle prototype made of powdered agar which, when mixed with water, forms a jellylike material that can be moulded into any shape. The designer says these bottles will continue to stand until they are drained, though the water may taste slightly salty after absorbing the agar.

In the same month, the most-discussed environmental start-up of late, Ocean Cleanup, launched three computer models to determine the locations and concentrations of plastic in the ocean in preparation for its mission to extract and intercept plastic pollution in the Great Pacific garbage patch in 2020. It also pencilled in its first trial early next year at the Japanese island of Tsushima.

The Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club recently announced it would no longer sell beverages in single-use plastic bottles, or provide members with plastic bags or plastic straws. This initiative took effect June 8 on World Oceans Day – a United Nations recognised annual day of celebration and action for the ocean.

“Reducing the amount of waste being dumped into our oceans is one of the challenges of our time,” says the Club’s Rear Commodore Sailing Anthony Day. “Here in Hong Kong, where recycling is effectively nonexistent, it’s impossible to sail far without being struck by the amount of plastic that finds its way into our waters and onto our beaches.

“I am proud of our cadets for showing the way through their successful initiatives promoting the use of reusable water bottles over the past three editions of Hong Kong Race Week and grateful both to our management and to our membership for now taking up the ‘plastic free’ challenge with effect from World Oceans Day.”

RHKYC’s initiative aligns perfectly with this year’s World Oceans Day theme of Healthy Oceans, Healthy Planet.

“It’s exciting that the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club and its membership will be significantly reducing their ‘plastic footprint’ and inspiring many more to do the same in their own lives and businesses,” says Bill Mott, Director of The Ocean Project that has been coordinating World Oceans Day globally since 2002.

“Congratulations to the RHKYC for taking the global lead in being one of the first yacht clubs in the world to stop using plastic in its operations, both with plastic bottles, and plastic bags. The ocean is what we all use for recreation as yacht club members, so it is very fitting that engaged leadership is shown to the broader community vis-à-vis ocean appreciation and improvement,” says Ocean Recovery Alliance co-founder Doug Woodring. “This move also sends a great learning message to our next generation of ocean appreciators.”

International Council of Yacht Clubs (ICOYC) President John McNeill also congratulated the Club. “Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club, as a founding member, leads again with this positive action toward securing the future, and showing the way for others in all corners of the world.”

On a national level, France banned all single-use plastic bags at the end of March and will extend it to all kinds of disposable plastic bags unless biodegradable – including those for packaging fruit, vegetables or cheese – by January 1, 2017.

Though plastic pollution is old news and has been a high-priority issue that has been driving initiatives ranging from international legislation and guidelines for industrial practice to local beach and seabed clean-ups, public awareness campaigns and plastic-bag bans, this has been a year of eye-opening changes, including motions and inventions that – for the first time – have many believing the future of the ocean may not be all that bleak after all.

The latest studies show that we dispose of around eight million metric tonnes of plastic into the ocean annually. In 2010 alone, about four to 12 million metric tonnes of plastic were washed offshore, or about 1.5% to 4.5% of the world’s total plastic production.

According to a Greenpeace study, 80% of marine debris comes from land-based sources, stemming from tourism-related litter such as food and beverage packaging, cigarettes and plastic beach toys; sewage-related debris like syringes and street litter carried down by waste water; fishing gear that commercial boats lost or dumped deliberately into the oceans; as well as waste thrown overboard from ships and boats.

The immediate victims are, of course, marine animals. Greenpeace says plastic debris affects at least 267 species worldwide, including 86% of all sea turtles, 44% of all seabird species, and 43% of all marine mammal specices and numerous fish and crustacean species that either become entangled in it, or mistake plastic debris for food and ingest it. The French Ministry of Ecology reports that 94% of the stomachs of birds residing in the North Sea are filled with plastic.

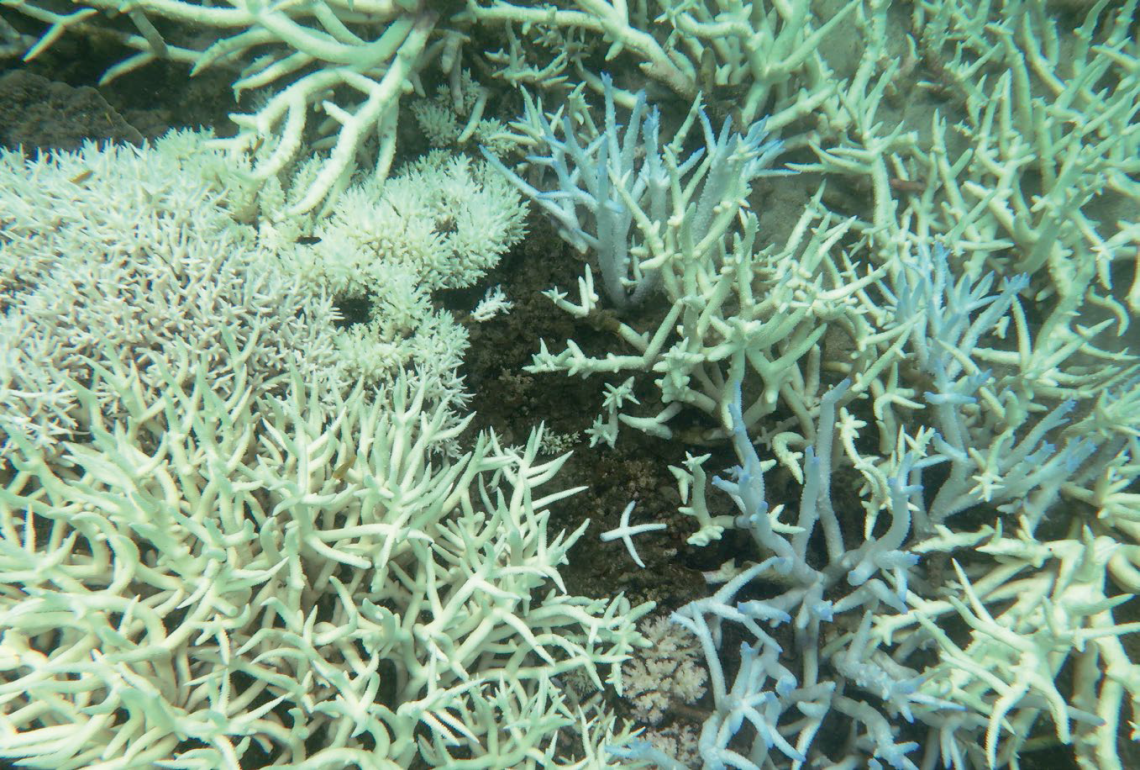

When the animals are not eating plastics, they’re getting caught in them – leading to death by drowning, starvation, suffocation or infected wounds, sometimes resulting in substantial population declines. Stationary species are also affected: nets and lines become snagged on coral, breaking off the heads as subsequent wave action pushes the debris along.

Bigger fishing gear, meanwhile, can trap animals large and small, causing decay and attracting more scavengers, which, again, may get trapped. In the early 90s, a 1,500-metre section of a net was found in the North Pacific containing 99 seabirds, two sharks and 75 salmon. The net was estimated to have been adrift for about a month, travelling more than 60 miles. Though worrying, these numbers do not include the victims that go undiscovered as they either sink or are eaten by predators.

Even when broken down, plastics continue to haunt the oceans. The presence of plastic on the seabed affects both the number and type of marine organisms that inhibit the area as well as the oxygen in the sediments, which can potentially damage the ecosystem. While invisible to the eye, they pollute our waters with chemicals like polystyrene, commonly found in plastics used for disposable cutlery, styrofoam and DVD cases, among other things.

A group that’s been actively keeping the waters clean is Ocean Conservancy. Eric DesRoberts, the group’s Trash Free Seas Program Manager, says there has been a steady increase of volunteers joining coastal clean-ups over the past 25 years.

“There’s definitely a sense of urgency when we start to make some of these findings more relatable,” says DesRoberts. “Since the global launch event, we have been encouraging folks to get out onto beaches and waterways to help pick up trash to keep debris out of the ocean and water system.

“Seeing more volunteers can be a good and bad thing: it means more people are becoming aware; but what we also need to think about is that by picking up more trash, the problem is not being solved. The real game changers are the industry players, scientists and people who can look at what we can do to stop trash from entering the ocean.”

One of those movers and shakers is WWF Manager of Packaging and Material Science Erin Simon, who brings 15 years of packaging and design experience from Hewlett-Packard to assist some of the world’s leading consumer brands like Coca-Cola Company, Danone, Ford Motor Company and Nestle with their roles in conservation, product protection, reducing biological footprint, ensuring transparency in supply chains, and better management in their products’ end-of-life processes so the materials remain valuable and can be recovered easily rather than reducing to just another piece of landfill junk. End of life, Simon adds, remains her biggest hurdle.

“First and foremost, [end of life] has a spotlight on it with plastics in the ocean being a very hot topic today: consumers are seeing waste in their pristine oceans so there’s definitely tons of pressure on the issue of waste management,” says Simon. “But waste is a lot more complicated than having a material be recyclable – we have to able to collect it, aggregate it, ensure that there’s infrastructure and a market on the back end that’s willing to buy the recyclable product.

“We need regulation, government support, resources, people and equipment; and we need to have consistency and a culture driving all of that. If you look at the United States and Europe, each country has variations within those steps: there are so many variables in question. The variability is just overwhelming.”

Though abhorring images of sea lions with beer rings around their necks would suggest otherwise, Simon argues that packaging is necessary not only in guaranteeing delivery, food safety and shelf life but also, for some countries, immense convenience. Certain rural areas in India, for example, only have communal showers – meaning soaps in sachets would make more sense than in bulk containers, though the prior is much harder to recycle and recover.

“I think consumers see packaging as this thing they throw away, but what they don’t understand is that packages are how they got the product safely,” she says. “Imagine going to get milk and you don’t have any jars: so will you pour the milk in your purse? Packaging is very underappreciated, so it’s definitely not a matter of eliminating all the evils that we know as packaging or plastics, but to force people and companies to ask real questions like how to improve their footprint or provide better solutions to achieve the same things plastics have been doing but in a more environmentally friendly manner.”

In 2012, Coca-Cola, Ford, Heinz, Nike and Proctor & Gamble announced a strategic alliance for the development of bio-plastic – whether in innovation, up-cycling or seeking out new commercial uses for these new materials.

Since then, Ford has spearheaded rice hull-filled electric cowl brackets and cellulose fibre-reinforced console components – all made with materials that are sustainably grown and locally sourced. Last year, Coca-Cola debuted the first PET plastic bottle made entirely from plant materials.

Increasingly, even the smaller players are getting into the game: Mitsui Chemicals launched a pair of bio-based high refractive index lenses made with plant-derived materials in May. A month later, green chemistry company Carbios and cereals giant Limagrain Céréales Ingrédients joined forces on the production of bio-based and biodegradable plastic films including green waste collection bags, mulch films, fruit and vegetable bags, industrial films and even mailing films.

While the list of green inventions can go on, there’s a reason plastic remains the choice material – its low production cost, durability, and some may even argue, minimal environmental damage. On average, only 5% of crude oil is used to make all the plastics we currently use, and plastic bags make up only 5% of that total.

Meanwhile paper bags, which are also usually single-use, demand four times as much energy and create 50 times more water pollution and 70% more air pollution. According to a 2011 report from the UK’s Environment Agency, a cotton bag would have to be reused 171 times to match the carbon dioxide pollution of a typical plastic bag – and this doesn’t take into account the pesticides used in growing cotton. Certain bio-plastics, on the other hand, require specific composting facilities for degradation and will likely breakdown at a similar rate as nonbioplastics in any other environment.

Yet, Simon believes it’s unfair to measure the new inventions with the same stick. “When you move from petroleum to an agricultural product you shift the impact. I think it’s easy to look at any new product and criticise; but the reality is we haven’t asked traditional plastics to measure their impact, we’ve never set that bar,” she says. “So now there’s a new industry that’s coming out that’s saying we’re going to try to do this better, we’re going to try to make materials that have a better environmental footprint, and the bar we have now has been set higher than it has ever been set before. But it can definitely be done.”

“Bioplastics take a long journey: the commitment is definitely out there, but it takes time for R&D because they need to meet all the requirements. We can’t just get rid of plastics but [we can] create a world with a mix of traditional, bio-plastics and recyclable materials in the marketplace. It’s going to keep evolving and we will keep asking industries to do more.”

www.bakeys.com

www.wwf.org

www.oceanconservancy.org

www.noaa.gov

www.livinglamma.com

www.raceforwater.org

www.rhkyc.org

www.theoceanproject.org

www.oceanrecov.org