The only family member still working for the dynastic Italian fashion house, Silvia Venturini Fendi talks to Lydia Slater about the needs of the modern woman and her inclusive fall/winter 2020 collection.

The only family member still working for the dynastic Italian fashion house, Silvia Venturini Fendi talks to Lydia Slater about the needs of the modern woman and her inclusive fall/winter 2020 collection.

A look from Fendi’s fall/winter 2020 collection

Even at a Milan Fashion Week rich in drama and spectacle, the Fendi fall/winter 2020 show was something special. Other designers presented their collections in cavernous auditoria accompanied by dazzling spotlights and a thumping soundtrack; Fendi ushered its guests into an intimate, softly illuminated boudoir furnished with gently curving velvet banquettes and a thick carpet, all in shades of rose. The clothes were tactile, padded and pastel, the silhouettes curvaceous, yet the models who strode the swirling runway exuded power and confidence. Silvia Venturini Fendi’s second solo womenswear collection was an uplifting celebration of femininity and feminism all at once, and it drew rapturous applause.

As it happened, the event was to prove memorable for another reason too: It was among the final few that took place under normal circumstances, before the coronavirus lockdown began and the fashion pack fled Milan.

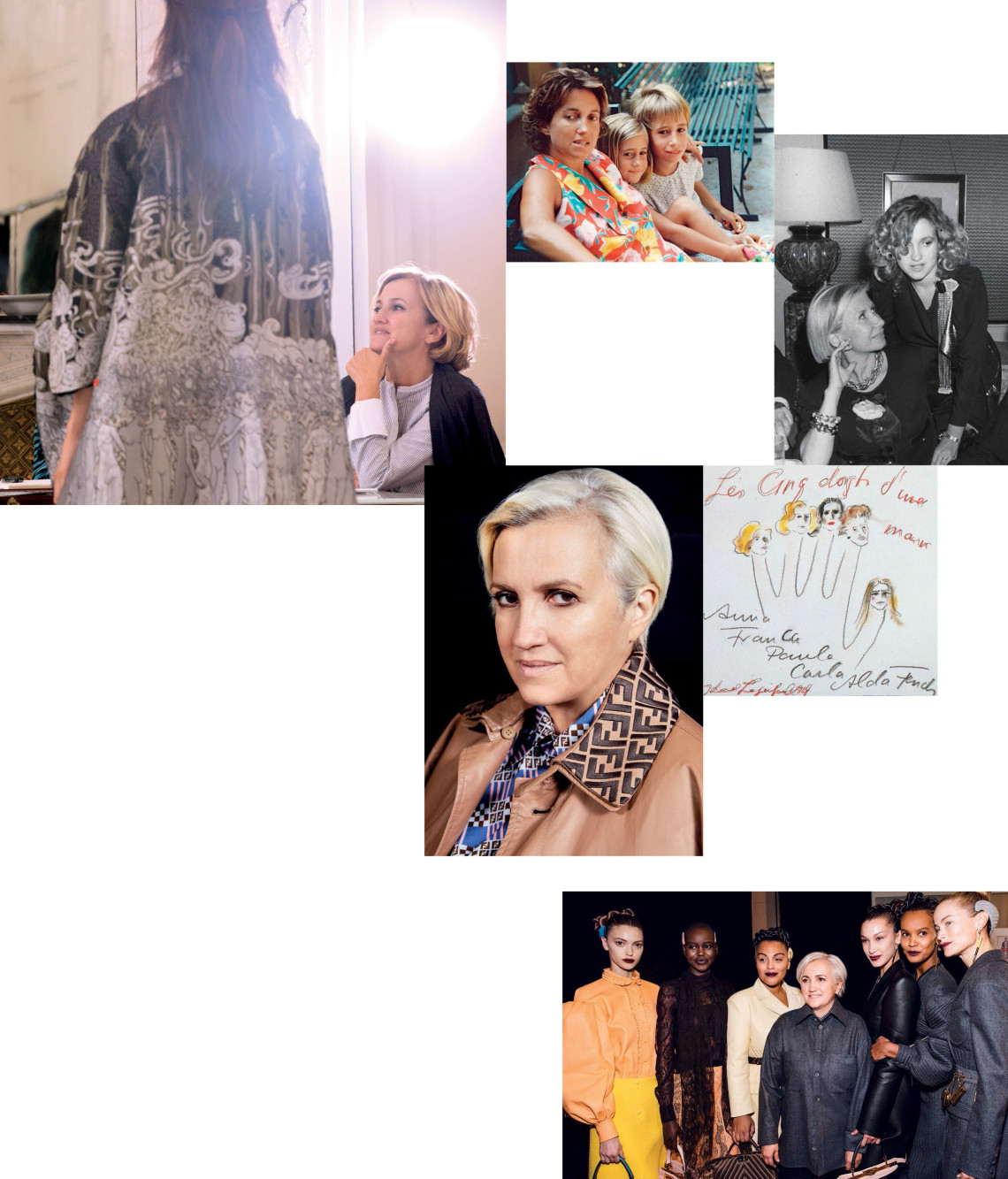

Clockwise from left: Silvia Venturini Fendi with Karl Lagerfeld at a fitting for the label’s 90th-anniversary couture show. Venturini Fendi with daughter Delfina Delettrez Fendi and son Giulio Cesare Delettrez Fendi in 1991. Venturini Fendi with her mother in the mid-1980s. A 1994 sketch of the Fendi sisters by Lagerfeld. Venturini Fendi backstage with models before Fendi’s fall/winter 2020 show. Venturini Fendi

“Yes, we were one of the last shows to have physical contact,” says Venturini Fendi when we meet (over Zoom) in her office on the sixth floor of Rome’s iconic Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana. She has been back at work for the past three weeks. Dynamic and warm, with a chic white-blonde bob, she is dressed with trademark understated elegance in a plain black jacket and a Fendi-motif shirt buttoned up to the neck. “Today, I see that show with a different perspective,” she shares. “We had a lot of dressing gowns and nightgowns on the mood board, so the idea of wearing something that feels good was in the air.” Equally, nothing could have been more timely than the inclusive casting, including older women, those of colour, and the first curve models to walk for the brand, Jill Kortleve and Paloma Elsesser. “Well, I’m not a super-skinny designer,” says Venturini Fendi with a chuckle. “It was a way of liberating everyone, but probably first myself. And I wanted to talk to women in a real way. As a female designer, you can really explore femininity. It’s a very mysterious topic; there are so many ways to portray it, and I wanted to express it through the casting. To [men], we’re nuns or b****es, the in-between doesn’t exist for them, really.”

In her own creative studio, female employees outnumber males by 10 to one. “This collection,” she says, “was the work of many women. It’s important, because for many, many years, fashion has been dominated by men.”

Fendi itself was a woman-led brand in the beginning, ever since Adele Casagrande opened a fur and leather workshop in Rome in 1918, which she renamed in 1925, following her marriage to Edoardo Fendi. “It was a little revolution right from the beginning,” says her granddaughter. She remembers Casagrande as a formidable figure who only wore shades of blue, adopted a single style of dress—a pleated chemisier with a scarf collar—and had shoes handmade by Petrocchi. “She knew what she wanted. She was the real boss of the family and I had so much respect for her... she was a very clever woman.”

The Fendis had five daughters, Paola, Franca, Carla, Alda and Anna, who jointly took over the business—deemed so important to Italy that the family was granted special dispensation by the government to pass their surname down through the maternal line.

As Anna’s daughter, Venturini Fendi was born into fashion—she loved to play in the atelier and first starred in a Fendi advertisement when she was just six. At the same time, she saw how hard her mother had to strive for her success.

Clockwise from left: Gigi Hadid backstage at Fendi’s fall/winter 2020 show. The fall/winter 2020 looks board. Peekaboo bag, $6,250; Mon Tresor bucket bag, Fendi

“She was working night and day,” says Venturini Fendi. “For a woman to be at the head of a company and to achieve what she did meant she had to work two or three times as hard as a man.” In order to toughen her daughter for a career in the same industry, Anna brought her up also “to fight”.

“My mother never bought me a pink dress; I was always dressed in trousers and dark colours—very strict, very Cal vinist in a way. When I asked her why, she said: ‘I had to prepare you to be less frivolous because I knew you had to work a lot and commit 100 percent to your work.’” (This inspired Venturini Fendi to highlight pink in her latest collection. “I wanted to explore this colour that was always considered the most banal sign of weakness,” she says. “I wanted to portray very strong women dressed in pink; I found it liberating.”)

Unconventionally, especially for 1960s Italy, it was her father Giulio Venturini, a civil engineer, who took up the domestic slack. “He was a very, very good cook,” she shares. “My father was more like a mother—he gave us lunch and picked us up from school. He was a good man, a modern man; he didn’t feel he was less powerful if he was going to the markets to buy food for us. At our school, he was voted the most handsome father, basically because he was the only one who came. I was very proud of that.” Sadly, he died when she was just 15. “My sisters and I felt really lost. It was very difficult.”

The other great male influence in her life at the time was Karl Lagerfeld, who, as a relatively unknown designer, joined Fendi to be its creative director when Venturini Fendi was a little girl. “I thought he was a magician,” she recalls. “It was incredible what he could do with a blank sheet of paper and a pencil—I never saw someone sketch so well and so fast. If Karl was there, instead of being at home with my sisters playing with Barbies, I would beg my mother to take me in.”

On his end, Lagerfeld was amused and intrigued by the child’s wholehearted fascination with his skill. “He knew from the beginning that my interest in him was very genuine,” says Venturini Fendi. “People think he was tough and cynical, but he wasn’t at all; he was very nice to children. I never felt like I was disturbing him. Never.”

Lagerfeld became part of the Fendi family and celebrated birthdays and Christmases with them. “When he started to work with others like Chanel, he had less time, so all those rituals were lost,” she shares. “But I have beautiful memories of when, besides the work, there was time spent for the pleasure of it.”

Clockwise from left: The Fendi sisters with Lagerfeld in 1986. Adele Casagrande, Venturini Fendi’s grandmother, in 1920. The Fendi sisters in 1985. Venturini Fendi working with Lagerfeld on fall/winter 2018 haute couture. Venturini Fendi fitting Bella Hadid for the fall/winter 2020 show

The strength of their relationship only grew as Venturini Fendi took a more active role in the company, launching the secondary brand Fendissime in 1987 and, in the 1990s, heading up Fendi’s accessories. “We talked a lot, we had personal jokes, but Karl knew he never had to ask me twice to do something.”

In 1997, she launched the iconic Baguette (so called because, with its oblong shape and short strap, it was designed to be carried under the arm like a French stick), which became the must-have bag of the decade and has since been produced in over 1,000 iterations. Sub sequently, she was asked to oversee menswear and the last family member to be working at the brand—in which LVMH took a controlling stake in 2001—was appointed interim Creative Director following Lagerfeld’s death from pancreatic cancer last year.

Venturini Fendi has clearly inherited the creative dynamism that runs down the maternal line. Though she always tries to balance her home and work lives, she found that lockdown provided a rare chance to relax with her extended family and children—son Giulio Cesare Delettrez Fendi, whom she describes as “totally anti-fashion”, and daughters Delfina Delettrez Fendi, a jewellery designer, and Leonetta Luciano Fendi, who is currently studying International Migration and Public Policy at the London School of Economics and, according to her proud mother, “wants to change the world. But I don’t know if she wants to do it through fashion.”

THIS COLLECTION WAS THE WORK OF MANY WOMEN. IT’S IMPORTANT, BECAUSE FOR MANY YEARS, FASHION HAS BEEN DOMINATED BY MEN.

At first, says Venturini Fendi, she tried to continue to work from home, but after the factories closed, she decided to abandon herself to the experience—“to have three months just for myself, and to listen to my needs and emotions. I felt as if I reconnected to my childhood; those long days with nothing to do, just daydreaming…”

She adds, though, that “there were very difficult moments. I didn’t see my mother for a very long time and I was worried about friends, but after the first 14 days, when we felt everyone was safe, we enjoyed it.”

She must miss her former mentor a good deal, at this time of combined challenge and opportunity, I suggest. Venturini Fendi nods. “I’ve been asking myself, ‘What would Karl do?’” she says. “He’d have taken the opportunity to reshuffle the cards. He was always ready to jump on new challenges and reinvent himself, so I’m sure he’d have come out of this renovated.” She herself has been energised by spending the past few months with her 13-year-old granddaughter Emma, Delfina’s daughter. “You don’t know how much she inspires me! She’s part of the new Generation Z—it’s interesting to try to detect what their needs will be. I’m trying to reflect on this.”

She lets on that she’s now “working on projects that don’t have so much to do with clothing, but will be Fendi products for real life”. She won’t say what they are, but has already spoken of her desire to create high-tech, medicalised garments, such as shoes that emit light to remind the wearer to keep socially distanced, or a t-shirt that monitors blood pressure.

“Everything that has happened has affected us so much that we’ll see it also through clothes, I think. I’m excited!” she concludes. With the recent announcement that her friend Kim Jones, current Creative Director for Dior Men, will be joining the House in February to oversee its womenswear—juggling, like Lagerfeld did, two major luxury houses at once—the rest of the world is equally excited. And if the latest chapter in Fendi’s history is anything like its predecessors, it will be well worth the wait.

PHOTOGRAPHY: MOLLY SJ LOWE; SCHOHAJA; AMBRA VERNUCCIO; COURTESY OF FENDI