Britain’s best-loved milliner describes the power of berets, bonnets and beanies to elevate the everyday to the extraordinary.

Britain’s best-loved milliner describes the power of berets, bonnets and beanies to elevate the everyday to the extraordinary.

Silk chiffon hat from John Galliano’s Dior spring/summer 2009 haute couture collection

Hats are the ultimate fashion expression. You can wear anything, however simple, but put a hat on and it becomes a look. It makes you feel so different and presented, and somehow, that carries you.

The great thing about being a milliner is the freedom. There’s such a wonderful variety of styles and inspiration comes from everywhere. I began making hats while studying at Central Saint Martins in 1976, in the era of punk. It was an extraordinary time, with a movement of like‑minded young people who didn’t feel represented by what had gone on before and had to find their own way. It was about not being mediocre: You wanted to be extreme. I was drawn to millinery because even though I loved punk, I also wanted to rebel against it in my own way and I realised that the archness of a hat could be as extreme as the archness of Johnny Rotten’s sneer.

Being part of a group of creative friends (known as the Blitz Kids) affected the work I was doing. In a way, we were competitive, but we were also very supportive of one another. If director John Maybury had a film opening, we would all think it was our duty to turn up; if Cerith Wyn Evans had an art opening, we had to be there; if BodyMap was doing a fashion show, we would go and help with it.

My greatest muses back then were people I made hats for: Diana, Princess of Wales, and the New Romantics—Boy George, Annie Lennox, Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet. Nowadays, I look to the Duchess of Sussex—an inspirational person who wears hats beautifully—and Rihanna, who has such a sense of fun.

When making a new collection, whether my own or for another brand, I first come up with the concept, the basic handwriting of it. Then, I lay out the designs into “chapters” before starting to sketch. I always have to find a balance between my original vision and the thing it wants to become. The creation develops its own character and if you try to go against the grain, it won’t work. There needs to be a natural, easy feeling to the process: Though architectural pieces can be very beautiful, those that have a certain softness, and a human face behind them, tend to be more flattering.

My work is always collaborative because a good hat is a combination of the design itself and the person wearing it. You have to listen to what the clients want the hats to do for them, whether it’s to look younger or more aggressive or more fashionable. The idea is that when they try on a hat, they’ll see themselves in the mirror and suddenly appear haute or romantic; they’ll put their heads down and flutter their eyelashes at themselves. Then they’ll look at me and laugh because we both know what they’re doing, and that’s the joy of millinery.

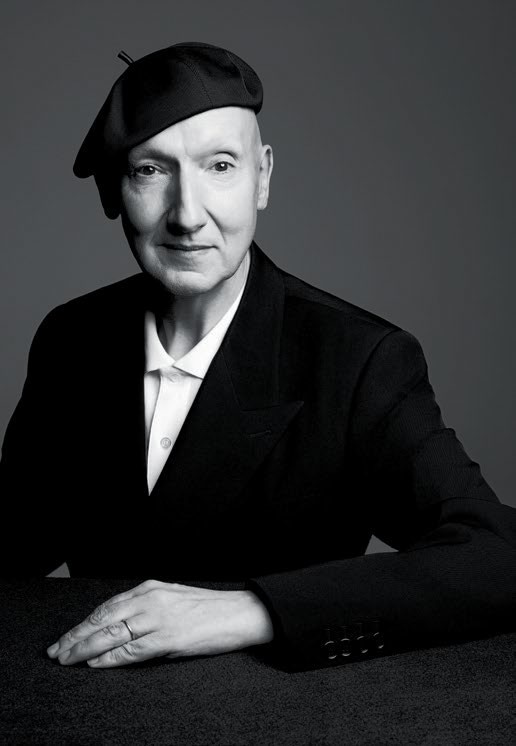

Stephen Jones

If I’m making a hat that will be sold in a department store, I don’t know the person who’s going to buy it, but I can still imagine him or her. During my training at a haute couture house, I learned to focus not only on the appearance of a piece, but also on the experience of wearing it, so I’ll always ask myself questions such as “Is this going to make people feel taller?”, “Is it going to make them feel good?”, “How is it going to go with their hairdo?”.

I studied womenswear at college, so for me, the relationship hats have with clothes has always been important: They add punctuation and rhythm to a look. I’ve been in the industry for 40 years and have a firm idea of what I think looks beautiful, but it’s great to join forces with fashion designers because they have a different vision, and it’s fascinating to be taken along with them. If you’re a fashion nut like me, it’s a great place to be. In a way, collaboration keeps you young because you stay aware of what’s going to come next. As the Artistic Director of hats at Dior, I’ve found it extraordinary to work with Maria Grazia Chiuri—just as I did with Rei Kawakubo for years. Maria Grazia loves hats and although she had never created them before she started working for Dior, she has always worn them. We’re very much building the designs together, two minds as one.

I can’t help but look to the past for inspiration. I get lots of ideas from the Dior archives, as there are so many hats there that have not been seen yet. Before he was a dress designer, Christian Dior made hats and they were the first pieces he sold. He’d either make a big, glamorous extravaganza of a hat or create something small and chic that continued the silhouette. Of course, in 1947, people wouldn’t wear a metre‑wide piece with five feathers on it for running around town or taking the children to school; they’d be more likely to opt for a beret. Still, I think a hat could be more individual than clothing because etiquette and the idea of being correctly dressed was quite limiting. You could have a little bit of veiling or a feather, or try straw or felt—each sends out a subtle message. Sometimes, it’s the simplicity of a piece that’s staggering. Yes, it may just be a plain black felt hat, but when you put it on, you think: “Wow, that line.” That kind of subtlety is true luxury.

I love the idea that now, we can have a hat wardrobe—with a pink creation for Ascot, a knitted beanie and everything in between. Hats follow society: Sometimes, people want mad extravagance and a fun party; at other times, they prefer modesty, being quietly special. But the most important thing is to put life into a hat. If I can experience something and somehow draw it on somebody’s head, that’s what I call a success.

Stephen Jones’s Dior Hats: From Christian Dior to Stephen Jones is available at kinokuniya.com.sg.

AS TOLD TO BROOKE THEIS.

PHOTOGRAPHY: SǾLVE SUNDSBǾ; COURTESY OF DIOR