Acclaimed Argentinean artist Julio Le Parc has spent the past 60 years dreaming up experiences exploring form, colour, light, movement and visual effects that engage all the senses.

After arriving in Paris in 1958, the intrepid artist dedicated his time to creating a unique style of visual art based on the concepts of Constructivism and geometry.

“On one side was the experience on the surface we were creating. On the other side was the viewer but there’s a third place that was the relationship between the eye and the surface,” he explains of the purpose of his works.

“Through my works, I have always sought to get spectators to behave differently,” states Julio Le Parc, 91, an emblematic figure in the history of art. “I wanted to find ways to fight passivity, dependency and ideological conditioning by helping viewers develop their ability to think, compare, analyse, create and act.” His recent limitededition table centrepiece collection for French porcelain manufacturer Bernardaud is a good example. Covered with a band of colour and textured lines that gradually progress in steps, Déplacement sur Plateau (Displacement on a Plateau) recalls his Displacement series sculptures with refiective blades that fragment and multiply the image to offer bewildering optic effects as a viewer walks around them.

Then there’s his signature Continual-Light-Cylinder, of which he has been making variations since 1962. Presented at his debut solo exhibition in Asia at Galerie Perrotin in Hong Kong earlier in the year and affixed to the ceiling for the first time, it gave visitors the impression of directly stepping inside the mesmerising and contemplative artwork as they lay on a mattress looking up at the construction of wood, superimposed rotating metal discs, lamps, Plexiglas mirrors and motors, which diffused fractioned light rays in a circle within a pitch-black space.

Drawing you in

At the heart of Julio’s multisensory works is the viewer experience and allowing the viewer to make sense of the artwork based on what he or she sees. “We began to do tests to find out if it was true that the public was unable to understand the art of its time. We started with the experience of the person looking and then from there, participation was solicited little by little with other experiences until active and refiexive participation. We realised that the public was very capable of appreciating what was currently being done or refusing the proposal.”

Blurring the line

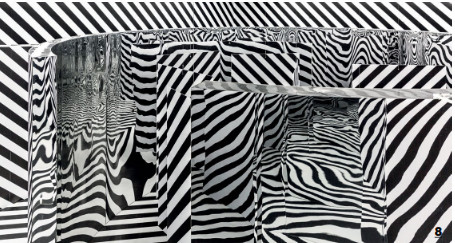

With increasing interest in the active involvement of the spectator and a goal of making art more accessible, Julio injects the notion of playfulness and visual instability into his pieces. Take for instance his labyrinth installations featuring black-and-white striped floors, ceilings and walls with mirrored structures that disorient viewers and challenge their spatial perception, or his Alchemy paintings, where multicoloured dots of pigment fan out across black or white backgrounds.

The man himself is filled with childlike energy and a cheeky sense of humour, creating daily in his light-filled atelier in Cachan, a Parisian suburb. There, a historical room showcasing 1960’s works resembles an arcade, encouraging all to have fun. Noisy machines whir, vibrate and rotate, mixing light and shadow, sound, movement and visual phenomenon, sometimes producing optical illusions. A slatted box hiding a mechanism casts light into horizontal lines on the wall, while projected light bouncing off hanging mirrored discs creates countless disco ball refiections.

From the start

Born in 1928 in Mendoza before moving to Buenos Aires at the age of 14, Julio was the son of a steam train driver. Attending the School of Fine Arts, with Lucio Fontana as one of his teachers, he engaged with the avant-garde ideas of NeoConcretism popular in South America, whose practitioners saw geometric abstraction as a political statement in opposition to the harsh reality of the military regimes of the period.

Leaving for Paris in 1958 on a French government scholarship because it was “the centre of the contemporary art world”, he met Op artist Victor Vasarely and began intimate painting studies in form, colour and movement with abstract compositions of geometric shapes that seemed to dance across the surface.

In 1960, he cofounded the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) with fellow artists like Morellet, Sobrino and Yvaral, and made his first reliefs and Continual Mobiles, taking his research into three dimensions and introducing movement and light. His light works – projected, refiected or pulsating – developed from his painting practice, as he was looking for new ways to show the constantly shifting character of depth and perception.

Of his style

Although Julio may be known as a forerunner of Kinetic Art and Op Art, he detests this simple classification. “The problem with categorisations like these are that they encompass everything and anything,” he discloses. “Sometimes I am grouped with people who don’t have the same behaviour or attitude of research, someone whose work is similar to what I have done, but is only a careerist, who has developed a style just to sell or gain recognition, too wrapped up in the system. But my approach is an attitude of research that has continued for a long time rather than one of becoming a monothematic artist, who has always done more or less the same thing for 40 or 50 years.”

Having been involved in the denunciation of totalitarian governments in Latin America since the 1940s, Julio doesn’t consider himself a political activist either. “No, it’s simply being a citizen; we can help,” he insists. “If there is a contact that is established between my proposals and viewers, and they leave my exhibition with a certain sense of optimism, that’s enough.”

The Goal

Less focused on commercial success, all Julio has ever been concerned about is keeping a little freedom for himself to make the art he desires, whether it’s a work on paper, painting on canvas, sculpture or even a virtual reality piece. Working with an artist-as-researcher approach, he’s happy as long as he can continually experiment in the creation of total environments using form, space, light and movement as aesthetic materials. His advice for up-and-coming artists? He replies, “Everyone must find their own way by refiecting on their situation and contemporary artistic creation, and try to find its contradictions in order to draw out something that is truly unique within themselves.”

9. Rolls of mirrored tiles are lined up to create a glittering effect in this installation.

10. Psychedelic colours evoke a retro feel in Julio’s studio.

11. Julio experiments with geometric designs to create eyecatching artpieces.

12. Julio expresses a futuristic feel in this illuminated piece.

14. Light filtering through this installation creates a stunning design on the floor below.

15. Viewers are invited to study Julio’s works from all angles during his shows.