Now entering its 131st year, Lalique has earned a reputation as one of the world’s great crystalware manufacturers, with its mastery of traditional techniques and understanding of light, transparency and colour that result in the creation of precious works of art.

Now entering its 131st year, Lalique has earned a reputation as one of the world’s great crystalware manufacturers, with its mastery of traditional techniques and understanding of light, transparency and colour that result in the creation of precious works of art.

Whether it was jewellery, tableware, perfume bottles, vases, objets d’art, luxury car mascots, furniture, lighting, wall decorations or architectural elements, visionary artist Rene- Jules Lalique, born in 1860 in Ay in the Marne region of France, was outstanding in everything he designed. He left his mark on the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements.

A leading figure in jewellery and decorative arts in the 19th- and 20th-centuries in his time, he was beloved both by royalty and the artistic elite. He had said: “I work relentlessly, with the will to arrive at a new result and to create something never seen before.”

Man with a vision

Hailed as the father of modern jewellery design, Rene apprenticed with jeweller Louis Aucoc and studied gold smithing and design at the Decorative Arts School in Paris, before working for celebrated brands like Boucheron, Vever and Cartier. He started his own business in 1888.

Inspired by classical antiquity, Japonism, Byzantine and Florentine art, nature and the female body, the avant-gardist ornamented his creations with unconventional materials, combining gold and precious stones with semi- precious gems, enamel, glass, leather, horn, ivory and mother- of-pearl. His philosophy was this: “Better to seek beauty than flaunt luxury."

Rene then moved into the glassmaking industry at the height of his jewellery career for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, thereafter abandoning jewellery-making in 1912 to concentrate solely on glass, tired of his jewels being counterfeited.

By 1920, he became known as a master glassmaker and, a year later, built a glassworks factory in Wingen-sur-Moder, Alsace – the only Lalique crystal production facility in well-forested at a time when Eschewing the multilayer, multicoloured glass produced by other glassmakers, he favoured clear and colourless glass and created forms displaying simplicity, balance and symmetry, by experimenting with the effects of transparency, opacity and opalescence inherent in the material. He filed 15 patents between 1909 and 1936.

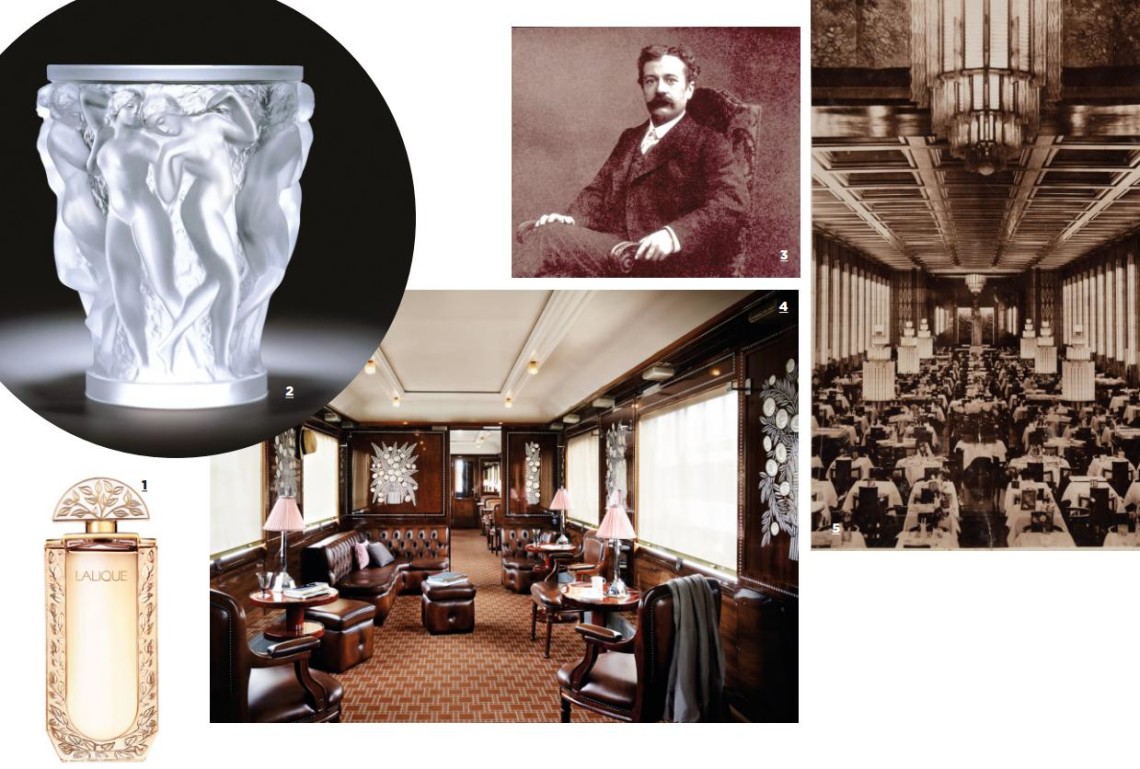

1. A Lalique de Lalique perfume bottle designed in 1993.

2. Bacchantes vase designed by Rene-Jules Lalique in 1927.

3. Rene Lalique in 1903.

4. Lalique’s Bouquets de Fleurs crystal creations are featured on the walls in the cabins of the Orient Express.

5. Crystal chandeliers gracing the halls of the Le Normandie ocean liner.

6. The Vesta necklace was launched in 2012, marking Lalique’s return to jewellery making.

Iconic beginnings

Some of his notable commissioned work include the design of decorations for the legendary Orient Express train and the ocean liner Le Normandie, the luminous fountain representing the springs of France mounted on the esplanade of Les Invalides in Paris, the doors of the palace of Prince Asaka Yasuhiko in Tokyo, and the cross, altar and windows of Notre Dame de Fidelite church in Calvados.

Upon Rene's death in 1945, his son, Marc, propelled the shift from mid-range, utilitarian glass to high-end crystal, and the Lalique factory has manufactured only crystalware since. Crystal is glass containing at least 24 per cent lead oxide, the ingredient that gives it its weight, brilliance and sonority. Other raw materials of silica, potash, cullet - and metal oxides for coloured crystal such as cobalt oxide to obtain blue are mixed in proportions that remain secret. With 230 employees, including six with the highly competitive title of Best Craftsman of France preserving ancestral savoir-faire, the 20,000 sq m factory produces half a million handerafted items annually

Forged in fire

It takes over a dozen years to qualify as a master glassmaker, and the finished product depends on the alchemy between the creative team's sensibility and the artisans' skills. Eleven in- house designers in Paris use traditional techniques such as drawing and modelling, and new technologies, thanks to digitalisation and 3-D printing, before the production process begins.

A single piece may require up to 40 steps. Lalique painstakingly fabricates moulds by machine, then adjusts them by hand, before glassmakers in the hot-glass workshops bring molten crystal in electric or pot furnaces to extremely high temperatures (1.400 deg C). After gathering, shaping, reheating and casting the crystal in the mould via various techniques (including blowing and pressing), the workers anneal it for one week, as otherwise the thermic shock would cause it to crack, shatter or explode.

In the cold-glass workshops, once retouching, cutting, sculpting and engraving are carried out manually, the pieces by sandblasting or plunging in acid baths. The parts that have received protective surface treatments remain clear, whereas the uncovered parts become frosted. The contrast between transparency and satin style; playing with light and shadow, it gives relief to pieces.

7. Zaha Hadid’s Manifesto vase in midnight blue.

8. Green Lalique vase designed by artist Terry Rodgers.

9. Dancing elephant in amber, designed by Rembrandt Bugatti for Lalique.

10. The Prism exhibition was launched this year at the Lalique museum.

11. Rene Lalique’s son, Marc, helmed the company, following Rene’s death in 1945.

Finishing touches

Enamelling and gold or platinum painting add touches of colour before the item is recooked at around 500 deg C, running the risk of deformation. Characteristic of Lalique, these cold-glass operations showing extreme attention to detail represent two thirds of the time spent on the manufacturing of each object.

Approximately half of all products are rejected during the hot-glass procedures and 5 per cent during the cold- glass ones. Items undergo at least 10 rigorous checks throughout the manufacturing process to ensure they satisfy quality standards in terms of technical (absence of defects) and aesthetic (faithfulness to the applied to certify authenticity

Created in 1927 by Rene, the best-selling Bacchantes vase decorated with female nudes in bas-relief calls for 30 work hours by 25 craftsmen. The large Anemones vase requires seven hot-glass workers, who gather 25kg of molten crystal, control the imprinting of the decoration, and ensure the good distribution of the crystal in the mould. This demands extreme dexterity and technical mastery, in terms of the mould temperature and the quantity of crystal. Eight persons and over two days of work are needed just for the cold-glass operations.

Intense sculpting work is carried out to redefine each anemone and remove seams, bubbles and other flaws, while manual polishing is an exercise in precision to reach the tiniest imperfections. Finally, 3,250 points of enamel are positioned freehand on the anemone pistils, then cooked at 510 deg C overnight.

Particularly complicated detailed, extra-large or unique pieces are cast using the time- consuming and costly lost wax technique used by Rene until 1930, which involves single- use plaster moulds instead of cast-iron or steel moulds.

This technique is widely employed for Lalique's artistic editions introduced in 2011, which places the savoir- faire of its artisans at the service of contemporary artists and designers like Yves Klein, Rembrandl Bugalti, Damien Hirst. Anish Kapoor, Terry Rodgers and Zaha lladid, who bring a new perspective to the brand.

12. Creation of Lalique’s glass and crystal pieces requires an entire team of artisans, from firing to finish.

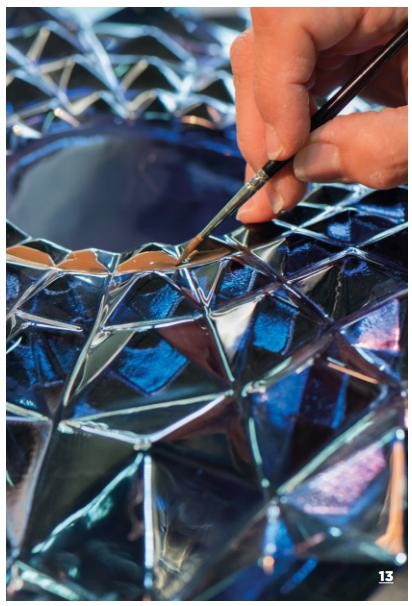

13. The process of applying enamel paint to the glass creations.

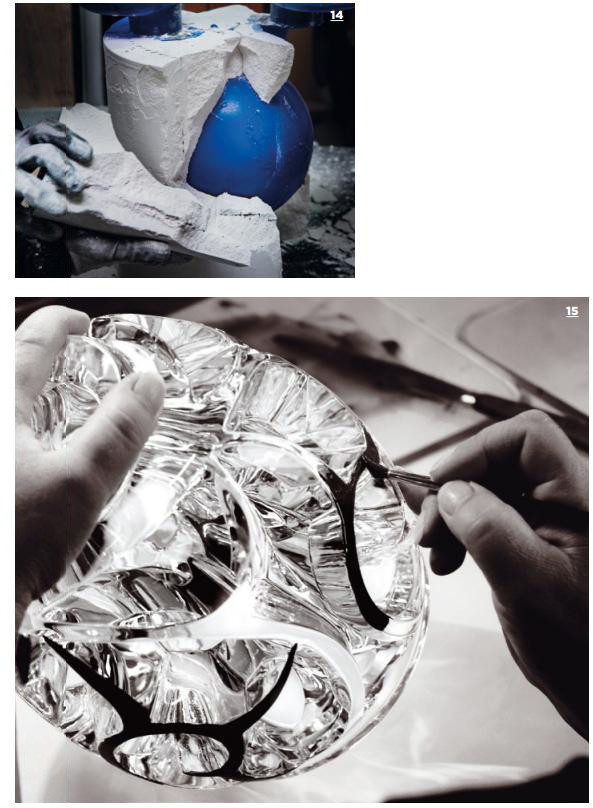

14. The lost- wax technique to shape glass involves the use of plaster moulds.

15. Five per cent of all glass creations are rejected during the cold finishing stage.

VILLA RENE LALIQUE

As Rene-Jules Lalique’s main Alsatian residence built in 1920, the villa in Wingen-sur-Moder reopened in 2015 as a five-star hotel with six exclusive suites, after four years of renovation.

Designed by Lady Tina Green and Pietro Mingarelli, it serves as a showcase of Lalique’s craftsmanship and creativity. The exterior was faithfully restored to its original appearance complete with blue shutters, while the interiors reflect the virtuosity of the master glassmaker, with each suite named after an iconic Rene creation and one named after his granddaughter Marie-Claude’s (right) famous panther, Zeila.

Highlights are the Hirondelles (swallows) suite in red and black with bunches of grapes on the crystal decorative panels, and lamps with bird motif – this was once Rene’s own room with views of his factory – and the Dragon suite, referencing the mythical creature with a sizeable balcony overlooking the peaceful 2.4ha park planted with hydrangea, and chestnut, birch, beech, oak, spruce and blue cedar trees.

Italian-made wooden furniture and accessories from the Lalique Maison Art Deco-inspired collections were used for the guest rooms, with pieces of crystal embellishing bed frames, dresser and bedside tables, armchairs, sofas, cabinets, mirrors and bathrooms according to each suite’s theme.

Chef Jean-Georges Klein runs the adjoining two Michelin-star, 40-seat restaurant with large glass bay windows, red Vosges sandstone columns and plant-covered roof built by Swiss architect Mario Botta, together with head sommelier Romain Iltis, who oversees one of Europe’s most extraordinary cellars housing over 60,000 bottles. Room prices range from 360 euros (S$565) to 890 euros per night.