The primordial stillness that reigns over New Zealand’s remote and pristine Dusky Sound makes an impression on seasoned traveller Victoria Burrows.

The primordial stillness that reigns over New Zealand’s remote and pristine Dusky Sound makes an impression on seasoned traveller Victoria Burrows.

“Paradise” is a grand word but it describes the primordial beauty of Dusky Sound.

I consider myself a jaded tourist. Under my own compulsion and as a food and travel writer, I have travelled far and wide across the planet, in planes, trains, hovercrafts and hot air balloons, taking in the most remarkable outputs of human civilisation and nature’s sublime beauty. All I have seen has influenced me in profound ways, for which I am extremely thankful. But the flipside of travelling so relentlessly is that you reach a point where it feels like you’ve seen it all before.

Every now and then, though, a place is so exquisite that it manages to wash away the fatigue, restoring a withered prune of a soul to a buxom plum. Dusky Sound, a rarely visited fiord on the remote southern tip of New Zealand, is such a place.

Reaching Paradise

Getting to the fiord is a thrill in itself. We took the helicopter from just outside Queenstown, a charming town adored by adventure-sports enthusiasts on the banks of “S”-shaped Lake Wakatipu.

We had left the comforts of Eichardt’s Private Hotel, with its giant beds and possum fur throws, in-room fireplaces and stunning sunset views, reluctantly at dawn, but all sulkiness evaporated when the helicopter noisily announced its arrival at the pick-up point. It swooped down to us, and we climbed into its snug interior with excitement.

Not entirely comfortable with heights, I felt a tightness in my stomach at the thought of being in a machine so small so high in the sky. But once we had lifted off, our pilot, Mark Deaker, head of aviation at Alpine Helicopters, and guide, Doug Beech, operations manager at Minaret Station – the remote, off-grid and helicopter-access-only ranch further north at Lake Wanaka – distracted me from my fear.

Focusing my attention on the wonders of the scene below us, Doug said through his headphones: “Lake Wakatipu is New Zealand’s longest lake, and one of its deepest, reaching down almost 400 metres.

“And there ahead of us, those beauties are the Southern Alps, backbone of the South Island.” The green-carpeted hills had turned white, and a fairytale of porcelain peaks pointed up through a bank of clouds. As the mountains got higher and the sun stronger, the morning moisture dissipated, leaving a jaw-dropping scene of glaring white against the deepest azure blue.

The chamois, while exciting to spot, is a nonnative animal that threatens the local habitat.

Mark guided the helicopter along the contours of the dips and heights, just skimming the higher peaks. At times I held my breath and lifted my feet off the cabin floor in reflex. As we were passing one particular slope, he craned his neck to the side and banked the helicopter down.

“Two chamois there to the right,” he said through the headphones. Then I saw them, two dark specks bounding through the snow on the impossibly steep slope.

“It’s a type of European goat-antelope, unfortunately one of many species introduced to New Zealand and threatening local habitats,” said Doug. “The Department of Conservation is working hard to protect native species.”

While New Zealand has no indigenous land mammals, it has bats and marine mammals, and native insects, fish, reptiles and frogs. But it is most well known for its unique, often ground-nesting (and therefore vulnerable to land predators) bird species, such as the famous kiwi, and also a cheeky parrot called the kea. The government has long had programmes of eradication for the rats, possums, red deer and many other imports that have brought native species of plant and animal to the brink of extinction.

The native flora of New Zealand is unique as it evolved in isolation for millions of years, and there are more than 700 plant species found only in Fiordland, with new species still being discovered – one of the reasons Fiordland National Park earned UNESCO World Heritage listing.

A Soundless Sound

From the air, the Park is breathtaking: Steep, emerald-green slopes plunge down into cobalt blue waters dotted with islands. And we were about to get a lot closer. “That’s where we’ll be landing,” said Mark, pointing to a small square of white on the water below.

As we banked down, the square revealed itself to be a floating barge, only barely – I thought with trepidation – big enough to land on. But Mark circled us down with ease and we touched down lightly. We climbed out, onto Dusky Sound, into another world.

The air was pure, with just the lightest scent of brine, and the sun shone warmly, reflecting off the water in glittering sparks. An occasional splash of water and birds calling from the densely forested slope behind us were the only sounds. Tethered to one side of the barge, the boat Storm Jet was waiting to take us out onto the water.

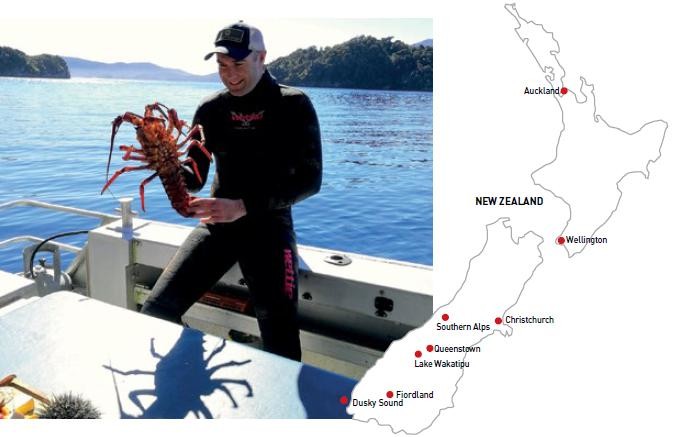

The water yields a feast of giant lobster and black abalone.

First, we stopped at a couple of small orange buoys bobbing in front of a steep rocky shore. Doug reeled in a basket of lobsters, by far the biggest I had ever seen. Holding one up, tail to antennae it stretched from his waist to above his head. We later stopped to fish, pulling in a variety of species, from the common sea perch to a baby shark, which we threw back if they didn’t pass lunch or fishing permit requirements.

To stretch our legs, we climbed ashore at Astronomer’s Point, where in 1773 Captain James Cook’s astronomer William Wales set up a temporary observatory using an H4 chronometer. Wales’s observations resulted in New Zealand being the most accurately located place on the globe at that time.

Beams of sunlight streamed between tall trunks of rimu (conifer), silver beech, manuka (which results in New Zealand’s world famous honey) and kahikatea (white pine), shining onto dinosaur-era tree ferns below – it was a primordial scene.

Mark cooked the fish and lobster for lunch, serving them only with a sprinkling of lemon juice. Also on the menu was sea urchin and paua – indigenous black abalone – for which Doug donned a wetsuit and snorkelling gear to prise them off the rocks. We ate the sea’s bounty sitting on the side of the boat, with local sauvignon blanc. The motion of the water and the perfect simplicity of the meal lulled us into a mood of dreamy elation.

Blissed out and a little tipsy, we watched the scenery sweep by alongside us as we headed back to our floating helipad. Suddenly the boat slowed and Mark shouted from the cockpit: “Dolphins!”. On cue, shiny bodies leapt from the water, lifting metres into the air. Dolphins raced alongside the boat, dived under it and playfully splashed with each other in the water.

“Is someone hiding a remote control?”, I thought to myself. “Am I on a movie set? How can a day be so perfect?” Even Doug, a regular on these waters, was thrilled and got out his phone to record the action.

Stunned by our luck and the sublime beauty around us, we headed back largely in silence – words would have broken the spell.

Also on the menu was sea urchin and paua – indigenous black abalone – for which Doug donned a wetsuit and snorkelling gear to prise them off the rocks.

All’s quiet save for the occasional splash of water and call of birds.

A Last Taste

For dinner, our chef prepared another giant lobster as well as some sea urchins that Doug had packed for us from Dusky Sound.

We stayed at Fiordland Lodge, just outside the small town of Te Anau. The lounge at the lodge, rich with native wood and stone, is a perfect spot to while away evenings in front of the fire, working through the library of books on fishing, hiking and Maori legends. Bedrooms may be simply decorated, but who cares for the fripperies of human design when you have the heart-soaring natural beauty of Lake Te Anau and the mountains behind through the floor-to-ceiling windows?

I sat on my balcony after dinner, wrapped in a blanket, sipping a glass of sparkling wine, and watched the stars come up over the distant snowy peaks with a sense of childlike wonder. Like magic, my jaded self had washed away somewhere into the silent waters of Dusky Sound.

A NATURAL PRESERVATION

The geographical isolation of New Zealand’s Fiordland, as well as its high rainfall, steep slopes and dense vegetation, has kept the area largely free of human habitation – and the damage that inevitably comes with it.

The Maori hunted and fished here from the 15th century, but it was in 1770 that the first European, Captain James Cook, sighted Dusky Sound. It is him we must blame for the inaccuracy of its name: It, along with Fiordland’s more famous and popular Milford Sound, is technically a fiord as it was formed by an ancient glacier.

In 1904, 10,000 square kilometres of Fiordland were set aside as a national reserve, and in 1952 it was formally designated as the third, and by far the biggest, national park in New Zealand. Fiordland National Park won UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 1986 and has remained largely untouched ever since.

MAIN PHOTO COURTESY OF MINARET STATION

PHOTOS COURTESY VICTORIA BURROWS AND MINARET STATION