African-American portraitist Kehinde Wiley on subverting the power relations embedded in certain art traditions.

Photo TONY POWELL

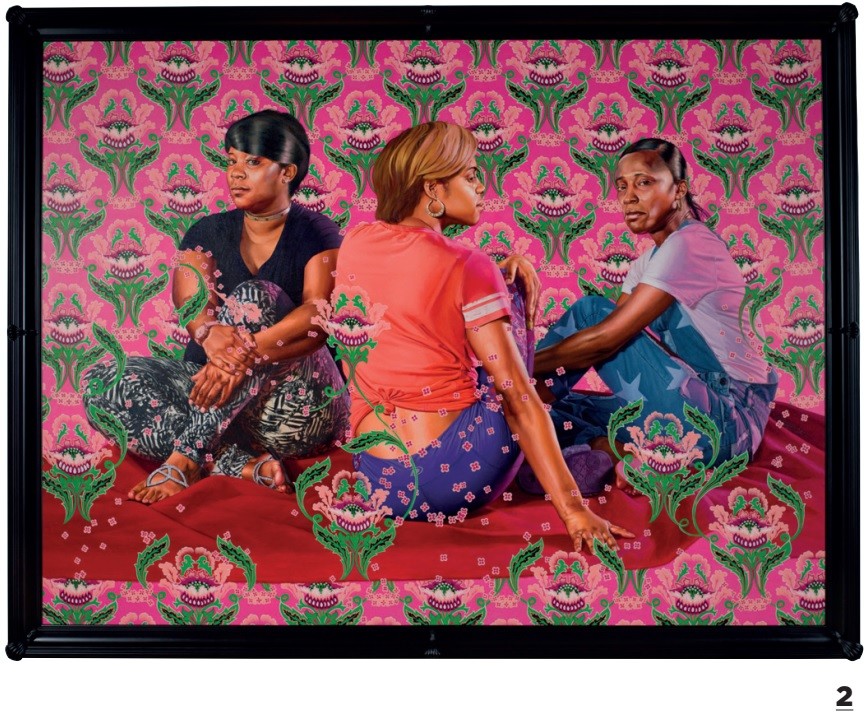

Known for his larger-than-life, hyperrealistic and richly detailed portraits that substitute depictions of aristocratic Europeans bearing symbols of power and status in paintings by artists between the Renaissance and 1800, with good-looking African-American men and women in modern-day clothes – T-shirts, sweatpants, jeans, sneakers and bandanas – striking confident, heroic poses, Kehinde Wiley has been subverting the power relations embedded in certain art traditions. The Los Angeles-born, Yale-educated portraitist confronts and critiques historical traditions that do not acknowledge the black cultural experience, thereby bringing Old Master paintings by the likes of Velazquez, Rubens, Titian, Van Dyck or Holbein face to face with contemporary popular culture.

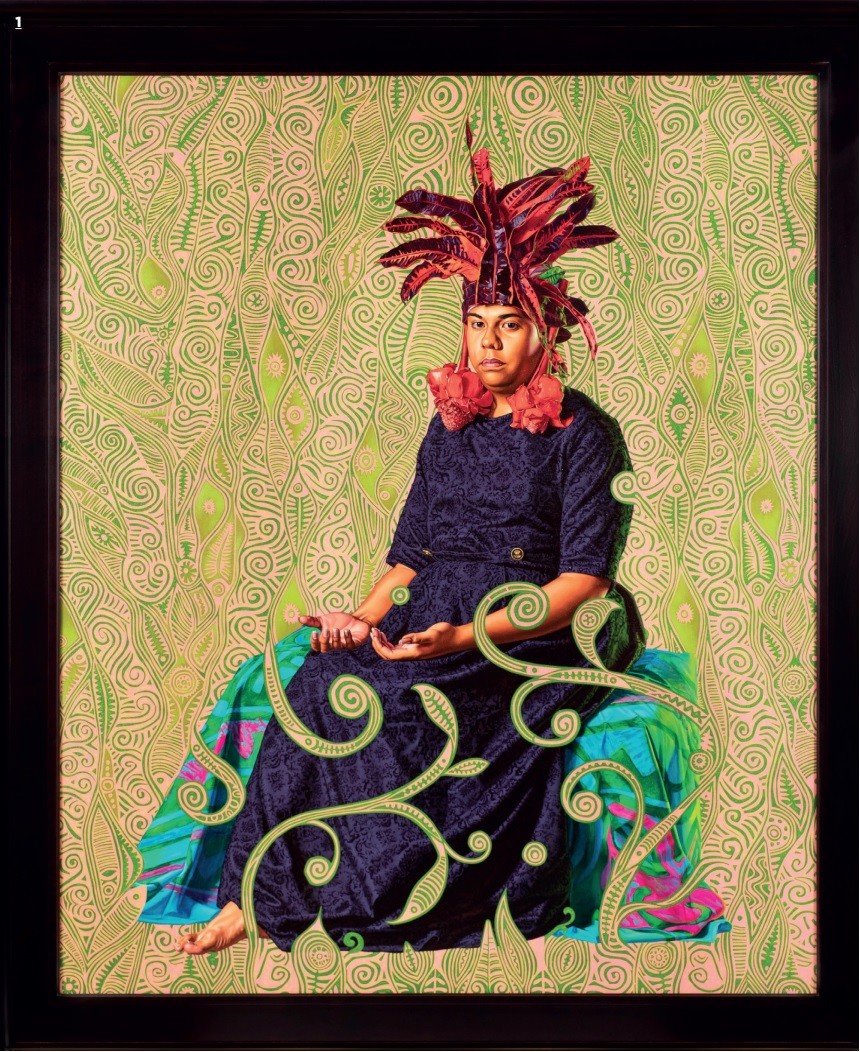

Portraying dark-skinned people from all walks of life, Kehinde – the first African-American artist to paint an official portrait of an American president (Barack Obama) for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery – has painted everyone from Michael Jackson and rapper LL Cool J to the ordinary man in the street and Tahiti’s Mahu third-gender community through the prism of Paul Gauguin’s masterpieces, which he presented in a 2019 solo show at Galerie Templon in Paris.

Harnessing the power of art to shift perception and to make visible history’s forgotten figures, Kehinde began his career by exploring African-American notions of masculinity and how black men were perceived in public and private spaces before adding women wearing flowing gowns and headpieces in empowering stances to his repertoire in 2012. In his unique way, he has been correcting the lack of non-white faces in Western museums, where people of colour have been typically excluded from representations of power.

His instantly recognisable subjects might be crossing the Swiss Alps on horseback in a nod to Jacques-Louis David’s equestrian portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte or seen as a haloed saint set against a stained glass window in place of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ portrait of the Holy Roman Empress in his investigations of religious iconography. Each body glows, permitting audiences to witness a state of grace for people rarely viewed in that way. They contrast with his unique backdrops of heavily ornamented patterns of flowers, leaves and vines representing the landscape, which are based on Victorian wallpaper, Baroque textiles or Renaissance tapestries.

“I KNOW THAT MY WORK HAS HAD AN EFFECT ON PEOPLE’S LIVES; I HEAR IT.”

– KEHINDE WILEY

1. Portrait of Moerai Matuanui (2019).

2. Three Girls in a Wood (2018).

Photo COURTESY ROBERT PROJECTS

3. Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005).

4. Kehinde filming in Tahiti.

5. His stained glass artwork Saint Adelaide (2014) was modelled after French artist Jean-AugusteDominique Ingres’ 1842 Saint Adelaide at Saint-Ferdinand Royal Chapel in Paris.

When I ask Kehinde why he chooses to place his subjects in a pose and history that are not their own, he replies: “Are they really, though? There is a swagger, a self-empowered knowing that you see in old European paintings. I love hijacking that language even though it exists already for many people I know and love; people who look like me. Many times, I’m able to simply show a type of truth that may not be public but personal – a type of poetry that is true.”

So is he paying tribute to or protesting against old Western chefs-d’oeuvre? “You’ve asked me a very important question about my relationship to history, to empire, to conquest and to art history, and I’m at once critical and accepting. It’s a beautiful and terrible history. What do I do with it? This new way of thinking about what the past was and how we move forward has to do with practicality. Artists are here to record the stories of our hearts, not our political stories but rather our interior stories, so we’re apolitical.”

He continues: “We’re looking up and down at the same time, we’re saying yes and no at the same time, we’re saying I love Gauguin, but it’s messed up at the same time. I’m trying to use my life – what I feel, what I like and what I’m drawn to – as an indicator of what’s important in the world, and if I feel something there, perhaps the audience will feel something as well.”

Dispelling preconceived notions about black people in America being reduced to 2-D caricatures that have nothing to do with the life he has lived, Kehinde – having grown up in poverty in South-Central Los Angeles as the son of an African-American mother and a Nigerian father he never knew as a child – is keenly aware of the cliches surrounding them. “It’s easy to go into stereotypes about the ghetto and to talk about SouthCentral Los Angeles as this dark place, but it was not,” he admits.

6. His 2019 exhibition at Galerie Templon.

Photo BERTRAND HUET/TUTTI

7. An interior design cocreated by Kehinde and Senegalese designers Aissa Dione and Fatiya Djenne.

Photo MAMADOU GOMIS

“There were aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, cousins, meals and celebrations. My self-image was shaped by my mother in many ways because, from a very early age, she found situations to place me in where I started thinking about myself differently. She demanded I go to Russia at the age of 12 to make paintings in the forest of Leningrad. I think if you look at most studies around childhood development, the existence of books in a family or house makes a huge difference in terms of the future outcomes of children’s lives, so I’m a perfect example of that. There’s something about what my mother was doing that was strangely different from the outcomes you see from many families in that community,” he adds.

Naturally gifted in art, Kehinde knew since he was young that he wanted to be an artist. “A lot of kids could draw,” he recalls. “We would compete with each other to make drawings of cars and comic book characters. My twin brother was a better artist than I was at the time. I think that what made it for me was a desire to stick to it; there was a passion. Is being good at something about talent or is it about time and just sticking to it? Not just the ability to say ‘I like this’, but rather ‘I’m obsessed with this, I’m doing this all the time’. I’m knocking my head like an autistic child against the wall every day doing the same thing. Why? There was no guarantee, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, that you would be a successful artist.”

He elaborates: “I knew that I was throwing my life away when I decided to move to New York and become an artist. I didn’t care. I wanted to be successful at being myself and I think that honesty is what people saw.”

8. The Virgin Martyr Saint Cecilia (2008).

9. The artist at work.

Photo HUMBERTO CONTRERAS

Now Kehinde has launched a multidisciplinary artist-in-residency programme – Black Rock Senegal – in Dakar. Since artist residency in Africa is uncommon, his manner of giving back and supporting new artistic creations that are multigenerational and cross-cultural provides young artists with a luxury retreat to make art while experiencing Senegalese culture.

It is, in some way, a reinvention of the experience he’d had when he first arrived as an artist-in-residence at Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001, while simultaneously creating a space to work outside of a Western context and in line with his heritage. “Maybe I have survivor’s guilt. I don’t know why I care so much, but I think it would be nice to do something cool, to work not in some ideational way but side by side.

“Black Rock stands as the direct answer to my desire to have an uncontested relationship with Africa; the filling in of a large void I share with many African-Americans. With this project, I wanted to explore my personal relationship with Africa while inviting artists to do the same, and to galvanise the growing artistic and creative energies that exist in Africa in an increasing measure with the addition of diverse, international, creative possibilities. I want it to get into the bloodstream, into people’s minds like a meme.”

At the end of the day, has Kehinde’s work somehow changed how black Americans are perceived? “It’s a big question. I know that there’s been a vibration. I know that my work has had an effect on people’s lives; I hear it. Social media is amazing because, in real time, people will tell you how your work has affected their lives. People have sent me stories about how they feel inspired to approach art or to see themselves differently. I think the short answer is yes, but I don’t want to make grand sweeping statements.

“I think art can function as a way of saying that no matter where we come from and no matter how different our lives or backgrounds are, there’s a way through; there’s a way to make contact. It’s a means by which we can reach each other.”

Text Y-JEAN MUN-DELSALLE Artwork Photo COURTESY OF TEMPLON PARIS & BRUSSELS