What exactly encapsulates Singapore style or design? We ask 20 creatives, each an icon in their field, what they think.

– ONIATTA EFFENDI, BAJU BY ONIATTA

The idea of a quintessentially Singaporean style, or local identity, has been explored throughout the nation’s history, but is still something so wonderfully fluid that most people cannot put a finger to it right away.

Yet, it is possible to immediately recognise something as “so Singaporean” when you see it. Whether it’s the iconic Vanda Miss Joaquim orchid, a poem on HDB void decks, a practical everyday item like the plastic carrier for a cup of kopi peng or our local brand of down-to-earth humour, there is a Singapore spirit that deeply resonates with people.

But what exactly is this Singaporean identity – and does it differ according to generation or creative discipline? In celebration of Singapore’s 55th National Day this month, we asked 20 creatives in the local arts and design scene to share their opinions.

A CONSTANTLY EVOLVING IDENTITY

To some, the Singaporean style is one that’s constantly evolving. “To me, it’s dynamic and fluid,” shares Oniatta Effendi, designer and founder of batik fashion label Baju by Oniatta. Natalie Mok, architectural executive at RT+Q Architects, agrees. “The core of Singapore design is to improve experience, and it’s increasingly reflective of innovation and creativity,” she says and cites RT+Q Architects’ House of Spice project as an example of the city-state moving towards architectural design for environmental sustainability. Think terraces for urban farming as well as natural insulation and optimised airflow.

Another thing that most creatives agree on is that design in Singapore will continue to adapt and evolve in a post-pandemic era. Becca D’Bus, drag performer and founder of Singapore drag revue RIOT!, muses that visual spectacle will be even more important now that online platforms have become the default – and our sensory experience has come to rely mainly on our eyes and ears.

For most, experiencing the arts is a dialogue of communal spirit and energy, something we have to work harder to achieve in a world without crowds. But there is hope. With its potential as a refuge for a shared identity among Singaporeans across the digital divide, design is more essential than ever. How exactly? “We are still searching for the answers,” says Tan Jia Yee, co-founder of creative studio In The Wild. “If we come together as a community and country, and have faith, we can adapt and learn to thrive alongside change.”

And it doesn’t matter if, in the end, the exploration never ends, and that we don’t have one single interpretation. Khairudin Saharom, founder of Kite Studio Architecture eloquently addresses this: “Sometimes, definition stifles exploration and creativity. Perhaps leaving it as something intangible might be what truly defines Singapore style.”

"The interior of Cure restaurant by Camiel Weijenberg."

“For me, Singapore style has shifted from the functional, basic and utilitarian purpose-built designs of the 1960s to 1980s to what we see today: an aesthetic that is more design-focused, taking the best of contemporary international designs and making them our own while respecting local heritage and conditions.” – CAMIEL WEIJENBERG, WEIJENBERG

SINGAPOREAN PRAGMATISM

Where would Singapore style be without a dash of the pragmatism or kiasu attitude we’re famous for? To twins Santhi and Sari Tunas, founders of apparel brand Binary Style, it’s an attitude of “practicality, convenience and sensibility with a hint of tradition”.

Perhaps this is best expressed in Singapore’s careful environmental planning that’s resulted in the flourishing garden city. While the detailed structuring may strike some as safe or boring, it represents the quintessential beauty of Singapore to others.

Hossein Rezai, founder of structural engineering firm Web Structures and the President Design Award’s Designer of the Year 2016, observes that Singapore has been designed in three levels: the detail level, the environment level, and the system level, citing the plastic carrier for our much loved kopi peng, the pruned rain tree canopy along the ECP and HDB public housing as respective examples.

Lee Tze Ming, one of the founders of multidisciplinary creative firm Stuck Design, says that good design should be very much connected to the way Singaporeans live. “We try to express this in our work while reminding ourselves to simplify, and to prioritise the question of ‘Why would someone use it’ before ‘What should it look like?’” he says.

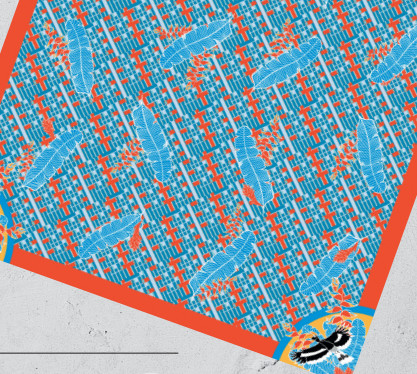

A Binary Style scarf featuring the iconic facade of architect Paul Rudolph’s The Colonnade and hornbills.

Santhi and Sari name the Shang System, a contemporary furniture system rooted in history and culture, bylocal furniture brand Scene Shang as an example of Singapore design.

"Jack and Rai at a live show"

“There is a Singapore style that exists but we think that it’s more like a philosophy. One that forms the basis of the way we think and do things, ultimately leading to how we behave and express ourselves. However, it isn’t original. Instead, it is an amalgamation of different cultures, from ethnic to pop, that influences the end product.”

– JACK AND RAI, SINGER-SONGWRITERS

A BLEND OF CULTURES AND TRADITIONS

The notion of a rojak of different cultural influences and identities is by far the most common thread when it comes to identity. Given Singapore’s history and our close ties with neighbouring countries, it’s not surprising to learn that most creatives feel that there is no singular attitude or approach to define Singapore style, but rather a colourful mix of the local and international, traditional and modern.

“Sometimes, as we are making an arrangement, we’d say, ‘This feels very Singaporean.’ And it can be for a variety of reasons. We do not fit into neat boxes!” says John Lim, founder of floral atelier The Humid House. This tapestry of cultural influences stretches across all creative fields, it seems, including art and music.

Artist Sun Yu-Li, who created the sculptures outside Suntec City and Singapore Art Museum, points to communal artworks as examples. For NDP51, for instance, he gathered 40,000 members of the public, who each added their personal interpretation of Singapore to a mosaic. “People draw something from memory or heritage, which contributes to the richness of the canvas,” he says. The mosaic is now on display outside the Singapore Sports Hub.

This expression of multicultural influences is also found in individual works of art. “The most consistent and recognisable has been designers’ reinterpretation of Singapore stories using visual icons from the architecture and objects that are uniquely Singapore,” shares Carolyn Kan, founder of jewellery brand Carrie K. One of her favourite designs features the diamond shape of the National Theatre built in the 1960s, a “gem we created together and which spurred our local arts and cultural landscape,” she says.

"Priscilla Lui and Timo Wong, the founders of Studio Juju."