LVMH’s successful foray into Chinese-made red wine didn’t come easy.

A bulldozer ploughed through a narrow street, shearing off a chunk of Maxence Dulou’s twostorey house in the process. The vehicle was en route to combat a hungry fire sweeping Shangri-la, the town where Dulou and his wife had just taken up residence.

There was no alternative; the Chinese firefighters’ access to water was restricted.

It was a cold January and the underground water pipes – laid to deal with such catastrophes – had been emptied by the authorities, for fear that they would burst from being frozen.

The bulldozer, with its ability to create a “break” in the flammable homes, was the only effective tool left.

Things work differently in China, the Bordelais winemaker reflects, as he recounted surveying the wreckage.

It is at this point that a lesser man might have regretted his decision to leave a cushy job in Bordeaux as winemaker of LVMH-owned Chateau Quinault, in Saint Emilion.

Dulou was there for eight years, learning the tricks of the trade from the team behind the legendary Cheval Blanc. Why give that up to head Ao Yun, then an unknown label from mountainous Yunnan, China?

“It is every winemaker’s dream to create something that’s never been done before.

Something that will be remembered,” explains Dulou, who’s now in Singapore to promote Ao Yun’s second release, the 2014 vintage. He’s leaning so far forward in his chair that I can almost feel the conviction and excitement emanating from him.

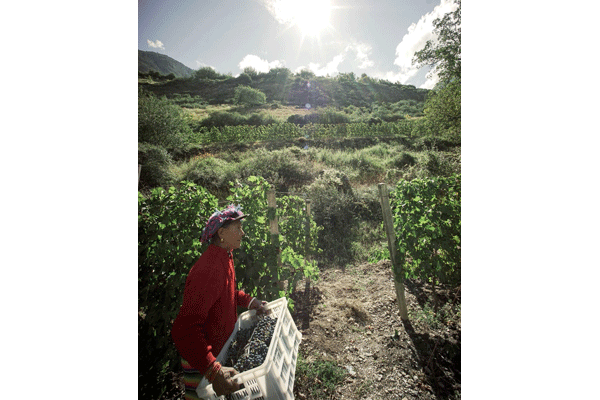

“It’s one big adventure.” Setting sights high The clarion call to establish LVMH’s next wine frontier came in 2012. Revered wine scientist Tony Jordan had just concluded an arduous four-year search across China for terroir that would be ideal for producing world-class red.

“(Northern) China would have been too warm in summer, so you’d lose a lot of freshness and acidity, which in turn reduces the wine’s elegance.

You’d also lose a lot of quality when you bury the vines in winter,” explains Dulou. “In the south, summer is too wet, so instead of ripening and producing tannins and phenolic components, (the grapes) are going to grow, so you have poor colour and structure. They’ll also be prone to a lot of diseases, which means they can’t be managed organically.”