AS A FOUNDING MEMBER OF THE SINGAPORE ART-MEETS-STREETWEAR LABEL MASH-UP, CO-HOST OF THE FASHION-FOCUSED PODCAST ‘IN THE VITRINE’, RESEARCHER, CURATOR AND FASHION LECTURER AT LASALLE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS DANIELA MONASTERIOS TAN OFFERS SOME WISE WORDS.

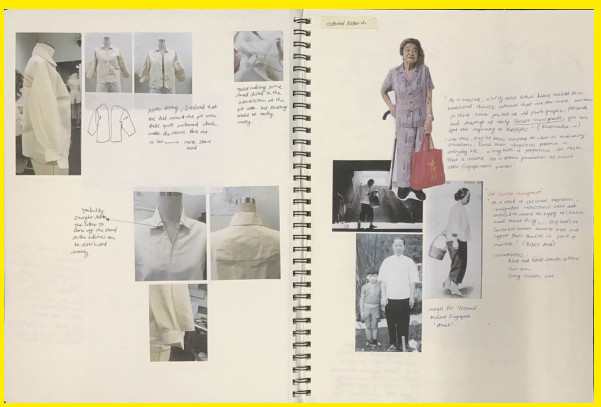

"There needs to be more synergy between fashion schools and the local industry in order to cultivate a more resilient ecosystem for aspiring designers, says lecturer/designer/researcher Daniela Monasterios Tan. Pictured here: an excerpt from the graduation project of her student Kim Se Na that explores upcycled fashion"

Having studied fashion yourself and getting involved in so many different parts of the business, how would you say that the scene has changed over the years for someone interested to join the industry?

“There are definitely more opportunities for jobs in bigger companies now than when I was a student, thanks to the digital revolution. Only after I graduated in 2009 did e-commerce become big with the likes of Zalora entering the Singapore market. There is also greater opportunity for exposure today with social media and more independent or online publications that are supportive of young, independent designers. Having said that, the retail scene was quite different about a decade ago. Then brick-and-mortar was still an important part of the shopping experience. There were many independent multi-label stores such as Blackmarket, Threadbare & Squirrel, Actually and Superspace (now Super Freak) with only the last two still standing. As a student, there were initiatives like Parco Next Next that was supported by the Textile and Fashion Federation and Spring Singapore, and encouraged young designers to start their own businesses. That’s how I co-founded Mash-Up with Nat Ng and Shaf Amis’aabudin in 2012. Now young designers don’t have as many avenues to do the same and have to fund themselves. Many of the independent designers from the time – Baylene, Woods & Woods, Nicholas – are no longer around and while students have the opportunity to work at larger companies such as Zalora and Love, Bonito, they are more commercial in nature.”

Are schools doing enough to equip students for the fashion industry?

“I’d like to think so. We try to teach them skills that work in parallel with their main classes. Fashion education is not just based on fashion, but also interpersonal and soft social skills that help them get jobs in related fields such as lifestyle and beauty. Singapore is a marketing-based economy, so (Lasalle College of the Arts) has also recently revamped our diploma programme to be more digital-focused, specialising instead in Creative Direction for Fashion – a first of its kind in Asia.”

What are the issues that the fashion industry is grappling with and how do you think fashion education can play a role in mitigating them?

“We are missing independent designers. Mentorship can be very helpful in creating a strong ecosystem and fashion education helps in bridging these relationships while the students are still in school. Singaporeans have to become the biggest champions for Singapore design, and retail platforms and support for Singapore designers have to be developed through outreach. Fashion education helps to get students to understand why fashion matters so that they can create businesses, images and designs that are thoughtful. This will help in producing graduates who will one day be in charge of leading the fashion industry.”

What about support for aspiring designers after they graduate?

“I think many of the (people behind) the fashion brands we see in Singapore today are actually self-taught and have business backgrounds. This works in Singapore, which is a very small and rather conservative fashion market with price-sensitive consumers. There is a rise in the number of entrepreneurs doing luxury resale and clothes-sharing that come from a tech or business background. What a graduate who is trained in fashion can add to such teams, I believe, is the eye for aesthetics, quality and fashion art direction. What I always say to my friends who are considering going back to school is that it is a safe space to dream and experiment, and to slow down your craft so that you can cultivate your unique point of view. In the grand scheme of things, school takes up only a couple of years of your life in comparison to the numerous years that you would take to develop your career. Of course support systems are needed to ease people into the real world with real consequences: budgets, timelines, customer feedback. That said, fashion education offers some of the most important forms of support systems from the industry. Overseas, for example, there are independent designers who invest in students’ work through bursaries and job placements. There are also various competitions that allow students to win prize money and traineeships. A friend of mine who studied at Central Saint Martins in London won a competition that gave him a six-month-long placement at Zara, allowing him the opportunity to test out his designs in a large market. He was also a recipient of bursaries and placements in independent labels that enabled him to design for higher-end consumers. These opportunities can only be realised if the industry and fashion education work together.”

What would you like to see as the future of fashion education?

“I am always excited to learn how my students view the world and want to express their views through fashion. I hope to see fashion education continue to offer a platform for students to freely critique and think about their identity and the implications of fashion. I hope to see these idealistic ideas translate into reality in the industry – ideas built around diversity, sustainability and ethics.”

A peek at the work of more of Tan’s students: Jane Nguyen Thi Van Anh’s exploration of traditional apparel favoured by Chinese grandmothers (above) and part of the mood board from Vita Nikolaieva’s witty and irreverent re-evaluation of modest wear – both driving across Tan’s words that the study of fashion is not just about design, but also culture