There’s something about deserts, those vast, seemingly empty stretches of wilderness that call to the soul. It’s no wonder hermits have hidden themselves away in deserts in search of spirit.

Finding yourself in Mongolia

There’s something about deserts, those vast, seemingly empty stretches of wilderness that call to the soul. It’s no wonder hermits have hidden themselves away in deserts in search of spirit. So when I heard that retreat company Reclaim Your Self was planning to take a group of yogi pioneers into the Gobi desert for Mongolia’s first ever yoga retreat, I couldn’t sign up quickly enough. I felt in need of some perspective on my life, a chance to step off the hamster wheel, to disconnect entirely from the madness of the modern world.

Travel writer Pico Iyer puts it perfectly: “The fact is that you can only make sense of the world by stepping out of it now and then. Something in most of us is crying out for a bigger perspective, a deeper wisdom, a stillness in the midst of all the exhilaration caused by movement and data.” Mongolia certainly has space aplenty. It’s a vast country with only three million inhabitants, most of whom are nomadic.

The Mongols were ecologists long before the word was invented and at the 1992 UN Earth Summit, Mongolia proposed that the whole country be declared a special biosphere reserve. They don’t believe in possessing land – they live in harmony with it and have a deep reverence for it. Most mountains are ‘holy’ or ‘sacred’ and every spring, mountain, grove and stream has its own spirit. This was going to be an adventure of the body, mind and soul.

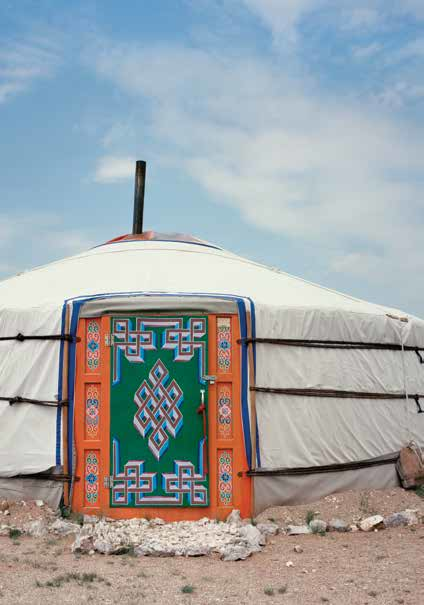

CLOCKWISE FROM BELOW: The t rans- Mongolian train; a Mongolian ger or yurt; the Mongol horse plays an important role in local traditional culture

DAY 1

Our group of 15 yogi pioneers have come from all over the world (Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, Myanmar, Russia, UK, Sweden) and we meet at Ulaanbaatar train station to board the trans-Mongolian. This isn’t the express, but a stopping train that barely breaks into a trot and for eight hours I sit and watch the countryside unfold, shifting imperceptibly from rolling hills and woodland to scrub to dust.

The skies are huge, the clouds low, flashes of lightning occasionally flicker over the horizon. It’s mesmerising. Then, abruptly, we’ve arrived and there’s a sudden flurry as we jump off the train. We’re nowhere and, as the train pulls away, there is the first sense of desolation, that primal fear of abandonment. Then a big old bus thunders into sight, barrelling along a dirt track.

We drive for a further two hours before reaching the Ikh Nart National Park and our base for the week. Rock formations thrust up like fists through the gritty scrub, forming a lazy circle around our camp. If the train stop was nowhere, Ikh Nart is the nowhere of nowhere. “Life here is simple,” says Reclaim Your Self founder, Jools Sampson, spreading her arms to embrace the wild desolation around us. “There is no contact with the outside world. You will be eating completely clean food and doing four hours of tough yoga a day.” She pauses.

“The more space you have around you, the more you discover in yourself.” The landscape is large but somehow not forbidding. The rocks around our camp feel protective, like a magic circle. I ponder just how insane it is that I’m miles from anywhere, hours from the nearest anything in the middle of a desert and I feel – safe.

We’re staying in gers (Mongolian for yurt) – some solo, some shared. Mine immediately feels like home, snug and cosy. It’s an enveloping, embracing space curved around a wood (or rather camel dung) burner. There’s no mains electricity here, no Wi-Fi, no phone coverage. I toss my phone into the bottom of my rucksack and lie back on my bed with a sigh of relief. A fire crackles in the burner, throwing wild shadows around the dome of the ger. I fall asleep to the rumble of distant thunder.

“The more space you have around you, the more you discover yourself” ~ Jools Sampson

DAY 2

I wake at 4am, head out into the night to the loo (a long drop out on the edge of the camp) and then stop in my tracks, awestruck at the Milky Way splattered across the sky like popcorn. I feel a sense of vertigo – the sky is so vast and I’m almost overwhelmed. It’s mesmerising but I’m glad to curl back under the felted blankets in my ger for a few more hours’ sleep.

A quick cup of fresh ginger and turmeric tea and then it’s time for yoga. Our teacher is Emma Henry, a renowned Jivamukti teacher from the UK. “This is tough yoga in a tough environment,” she says with a smile. Jivamukti is a strong, athletic practice (it developed from ashtanga, a very dynamic form of hatha yoga) and as we move through swift sun salutations, I feel clumsy and slow, inflexible and lacking in grace. Emma explains that we’ll be working through the chakras, starting with the root. “The root chakra is about survival,” she says.

“It’s hard to come into the world safely – no wonder it’s called labour.” My life lately has felt like a permanent struggle and I start to worry. Will the desert be just too tough, too uncompromising for me? Should I have gone somewhere softer, gentler, kinder? Do I really want to labour? The second yoga session seems to confirm it. I just can’t do it. My arms won’t obey. My legs go feral. I start to cry and suddenly I can’t stop. I get up, stumble out and retreat to my ger. I want to go home. Jools pads in and we talk. “Nearly everyone has a bit of a meltdown,” she reassures me.

This page : Life is simple in Ikh Nart. opposite page : Jivamukt is a strong, atheltic practice; camels roam freely on the outskirts of the camp.

“You won’t be the only one, that’s for sure. There’s something about coming away on retreat that brings things up, that acts as a catalyst. And that’s going to be even more pronounced out here.” I know she’s right but I still feel a bit bereft. I wander off and sit on a rock, looking out into nothing. Then I pull my focus in, gazing down at my feet. Up close, the Gobi isn’t barren – the ground beneath me is studded with tiny star-like white flowers and tufts of tough grass. A lizard looks quizzically at me. And it strikes me, as the shadows lengthen and the warmth turns to chill, that this place is only as desolate as I choose to make it.

DAY 3

We’re working with the sacral chakra today – with creativity, the emotions and sexual relationships. “We’re focusing on the hips,” says Emma. “Hip opening and closing, forward bending – our hips hold so much emotion.” She leads us in a chant to the fiery forceful goddesses Kali and Durga. “Take away all that is not free,” we chant. That sounds good to me. After breakfast we lie outside for meditation. A soft breeze tickles my skin and birds fly low over my head, with a soft whup whup whup. I can hear voices calling in Mongolian, laughter, the grunt of a camel.

I start to relax. In the afternoon I make my way to the massage ger.

There’s a blast of hot air as I walk in from the fire; sandalwood lies

sweet and woody on the air. Jools not only runs the retreats but also

offers her own brand of hot stone and deep tissue massage. Her touch is

assured, deep yet comforting and nourishing. Every so often someone

quietly pops in to top up the fire with a few new camel pats but I

couldn’t care less – I’m off floating in bliss. Evening yoga is a yin

session so I’m able to stay in my little bubble of quiet meditative

serenity. Yin yoga is slow yet deceptively strong.

You sink into a posture and stay, using a very light ‘ocean breath’ to find your edge and examine how the body releases. “Commit to being still,” says Emma as we sink into a forward bend (supported by big felted cushions). “See

what comes up.” She chants lightly and I feel my body relax and let go a

little more. That evening, I sit back on the rocks, watching the sunset

fall. Birds chase wind currents. I let out a deep sigh.

This page : Inside the snug, cosy ger. opposite page : Jools offers her own brand of hot stone and deep-tissue massage

DAY 4

This really is the ultimate detox. It’s not just the yoga that’s cleansing our bodies and minds, but the food too. Mongolian food is notoriously meaty (travellers’ tales of chewing on lamb bones and being served sheep ovaries abound) but Reclaim Your Self has brought Emma Fountain, a vegan chef from Cambodia, to pull off the nearly impossible – cooking gluten- and sugar-free vegan food in a tiny kitchen ger on a simple stove with no electricity for mixers and blenders. It’s delicious, light yet comforting with surprising smashes of flavour.

Today we’re moving further into the wilderness, to a temporary ger camp set against a backdrop of rocks where a lama used to meditate in the 13th century. I start off riding on a camel, one of the herd of two-humped beasts that wander freely on the outskirts of our camp but after an hour, my backside is numb, and I hitch a lift on one of the camel carts instead. Camels seem to go at one pace – death march slow – and the majority of our group are walking, but I am sinking into this slower pace of life and enjoy watching the landscape unfold in its own time.

The lama’s rocks form a natural amphitheatre and we perch on rocks and meditate, blessing all the people we know – from close ones, friends, family to acquaintances and even people we don’t know. A feeling of immense tenderness swells up in me, for even the most difficult people. Then, as the sun starts to set, a fire is built. It lights quickly, a wild, frenetic, eager, gusting thing, shooting out sheets of flame. Emma sings kirtans in this sacred spot. We sip tea and watch the shadows lengthen and the swallows dip and weave like slingshots. It’s a beautiful night.

“Be happy for those who are happy, be compassionate for those who are unhappy; delight for those who do well; be indifferent towards the wicked” ~ Patanjali.

DAY 5

We stumble out to salute the sun as it slinks up over the rocks. It’s wonderful to be outside for yoga practice and I watch, fascinated, as a beetle slowly and calmly makes its way across my neighbour’s mat, somehow avoiding her moves. One of the local guides sets off cross country and we follow. He walks in a straight line, rather than following a track, guided by his inner navigation.

We clamber over rocks, march over uneven desert. Vultures, wingspans of giants, float overhead. The breeze has dropped. It’s hot. I’ve only been away from my ger for one night but my heart sings when I get back to camp. Nature is so vast here yet, curiously, you don’t feel so alone. Maybe because, unlike other wilderness, people live here. This is a land where people have personal relationships with rocks. I’m beginning to understand how that feels.

DAY 6

I’m sitting on a rock again, enjoying the warm soft wind caressing my skin. I’m moving even more slowly now, feeling an even deeper connection to the earth. I’m noticing each individual stone, each patch of grass and walking between it lightly with care. I lie back against the rock and let myself sink down into it, opening my heart and staring up at the sky. I feel like I’m on one of those fairground rides, where you’re held by centrifugal force.

Lying on a rock in the Gobi, watching the universe spin by. I start to laugh, my throat chakra releasing. I walk on and find another spot. The new place is not so comfortable. A spike digs into my spine, another into my arm. Is this earth acupuncture? I experiment. It feels good. I ask the earth to heal me and I can almost believe it will. Come evening we sink once more into yin yoga. This feels good – the yoga of the earth, the feminine, the yoga of letting go.

This page : The desert gives one a stronger sense of self. opposite page : Though challenging, practising yoga in a tough environment such as the Gobi desert can be an inspiring experience.

DAY 7

It’s the last day and we’re up in our heads, looking at ‘citta’, mind stuff. We’re sitting in the yoga ger and Emma is reading from the yoga texts of Patanjali. “Cultivate a blessed mindstate,” she says. “Be happy for those who are happy; be compassionate to those who are unhappy; delight for those who do well; be indifferent towards the wicked.” It’s a lesson about not getting riled up; about being compassionate and kind. “You can handle any situation if you have the right keys in your back pocket for all the locks,” she says.

I ponder this as I move through the session. I am not an athletic yogi – I can’t jump into chaturanga or balance on my arms or hands – but it doesn’t matter. I am what I am and I decide it’s time I gave a little compassion to myself, to my body and my mind. The desert has taught me patience and given me a stronger sense of who I am and who I am not. As we drive back to Ulaanbaatar, I watch the rocks, nodding a salute to my favourites, a sensation of loss tugging at my heart as we move away – it’s like leaving friends. As we leave the Gobi, I see a cloud shaped just like the Sanskrit for om. It feels like a benediction. www.reclaimyourself.co.uk; www.nomadicjourneys.com