As the old Chinese proverb goes, “Gold has value, but jade is priceless”. Here’s why.

Once the preserve of the Chinese elderly and souvenir shops peddling “exotic” treasures from the Far East, jade has a reputation for being dated and less glamorous than its sparkling gemstone cousins. But, as with most things in the luxury circuit, rarity breeds interest, and dwindling supply from Myanmar – which supplies over 70 per cent of world’s high-quality jadeite – has driven prices up.

In 2017, Christie’s sold a necklace composed of 29 jadeite beads with a ruby and diamond clasp for HK$95.7 million (S$16.6 million). Three years before that, a similar necklace made by Cartier and once owned by Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton sold for US$27.4 million (S$37.1 million) at a Sotheby’s Hong Kong auction, breaking the record for the highest price ever paid for a jadeite jewel.

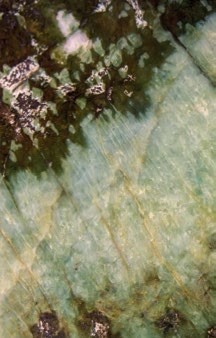

Such necklaces have simple designs because the stones themselves have a unique beauty. Its fine crystalline structure lets light dance through, reflecting and refracting rays in a way that makes its translucency look like water within the stone. And because of how jadeite forms in thin seams, it is immensely difficult to cut and polish identical sets of beads. Finding enough to make a string of homogeneous, flawless, vivid green beads is akin to finding natural pearls of the exact same size and shade.

Even on its own, jade is an enticing material for designers to work with.

JADEITE

Jadeite is a sodium aluminium silicate material from the pyroxene group. Because of its chemical composition and crystalline structure, jadeite tends to have greater translucency and lustre than nephrite, and is also slightly harder and more scratchresistant, reaching a seven on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness.

It is most commonly represented by the emerald-green variety, which the Chinese call fei cui, but can come in a variety of colours like black, white (left), red, pink, orange, purple and blue.

Jadeite was introduced to China from Myanmar (then Burma) in 1784, and gained popularity during the Qing dynasty in the 19th century. During this time, Empress Dowager Cixi became enamoured with the stone, leading officers and the nouveau riche to follow suit, in trying to acquire as much of it as possible. It is rarer and now also more valuable than nephrite.

NEPHRITE

Nephrite is a calcium magnesium silicate from the amphibole group. Its dense structure means it’s actually tougher, less easy to break than jadeite, though loses out a little in terms of hardness, being 6.5 on the Mohs scale.

This was the stone of ancient China, where nephrite from deposits in Sino-Central Asia (now the province of Xinjiang) were brought to the mainland to be carved since at least 7th millennium BC. It comes in pale shades of green (left), yellow, gray and even light brown, but it is the creamy white form – known as “mutton fat” jade in China – that was most prized among noblemen and scholars of that era.

Because of nephrite’s even greater array of available colours, pieces from ancient China were often variegated, rather than being one solid colour throughout. In order to achieve chalky, ivory-like whiteness, nephrite must be exposed to extreme heat of about 1,025 deg C, which results in “chicken bone” jade. On the other hand, when jadeite is heated, it turns glassy and may melt out of shape.

MAKING THE GRADE

According to Hong Kong jeweller Dickson Yewn, one can select jade either by emotional resonance or by the quality-price index of major dealers and auction houses. “This is the best way to learn about jade’s quality,” he says. If you’re leaning toward the latter, here’s a primer to get you started.

01 TYPE A

The jade has not undergone any form of artificial treatment to enhance its appearance or durability, except for surface waxing. Type A green jadeite with almost glowing translucency is the most valuable, and is known as “imperial jade”.

02 TYPE B

Slightly stained jade may be bleached or exposed to acid treatment to remove impurities and improve the colour and translucency. Because the texture of the jade gets damaged during the process, the gaps are filled with a clear polymer resin. Infrared spectroscopy will be able to detect the presence of polymer.

03 TYPE C

Chemically bleached or dyed to enhance the colour of green, lavender, yellow or red jade. If not done properly, the stone may wind up a dull brown. Regardless, Type C jade has a tendency to discolour over time if exposed to strong light, body heat or household detergent.

04 TYPE B+C

Basically a combination of the processes involved in creating Type B and C jade, where the stone is both impregnated with resin and artificially dyed.

05 TYPE D

The most inferior grade can be jade that is as thin as a piece of paper, but backed with resin to enhance its colour and transparency. If very little jade is used, it is mounted on a plastic backing.

Forget pea pod and buddha-shaped pendants. These jewellers show that jade has a place in modern luxury.

Cartier’s record-breaking jadeite necklace needed a simple design to augment the natural beauty of each bead, but when the jeweller’s full creative abilities are unleashed, the results can be wonderfully contemporary. This high jewellery object presents a nephrite jade case, with a clasp adorned with a sapphire, ruby and emerald arranged into the maison’s Tutti Frutti leaf design. The jade box may be worn as a pendant, while the Tutti Frutti motif can be worn as a brooch.

ORIGINS

WALLACE CHAN

YEWN

SUZANNE SYZ

CHOO YILIN

Preferring to use the paler shades of Type A jadeite, Singapore’s own Choo Yilin has won fans (over 20,000 of them on Instagram at least) with romantic collections that include a touch of local flavour. The Warisan Kebaya collection, for instance, recreates the traditional motifs of kebaya in 18K rose gold filigree and milgrain and pairs them with icy jade.